Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 time period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger.

Warship Wednesday, April 14, 2021: Just a Little DASH

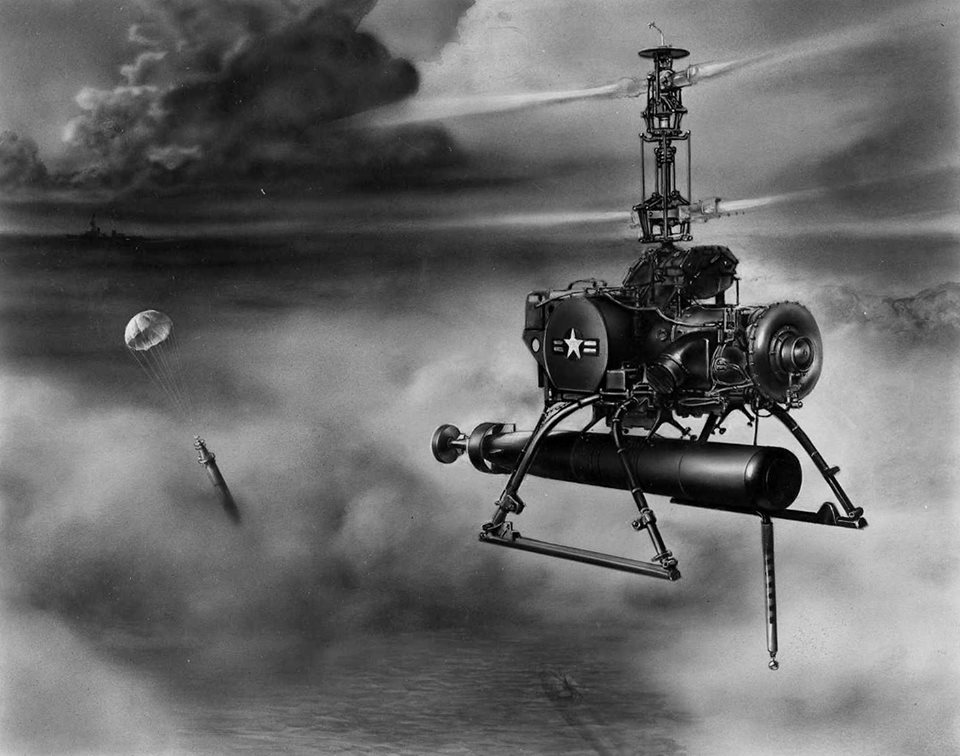

Here we see a great original color photo of the Fletcher-class destroyer USS Hazelwood (DD-531) with an early torpedo-armed Gyrodyne-equipped Drone Anti-Submarine Helicopter hovering over her newly installed flight deck, 22 March 1961. Hazelwood was an important bridge in tin can history moving from WWII kamikaze-busters into the modern destroyers we know today.

Speaking of modern destroyers, the Fletchers were the WWII equivalent of the Burke-class, constructed in a massive 175-strong class from 11 builders that proved the backbone of the fleet for generations. Coming after the interwar “treaty” destroyers such as the Benson- and Gleaves-classes, they were good-sized (376-feet oal, 2,500 tons full load, 5×5″ guns, 10 torpedo tubes) and could have passed as unprotected cruisers in 1914. Powered by a quartet of oil-fired Babcock & Wilcox boilers and two Westinghouse or GE steam turbines, they had 60,000 shp on tap– half of what today’s Burkes have on a hull 25 percent as heavy– enabling them to reach 38 knots, a speed that is still fast for destroyers today.

USS John Rodgers (DD 574) at Charleston, 28 April 1943. A great example of the Fletcher class in their wartime configuration. Note the five 5″/38 mounts and twin sets of 5-pack torpedo tubes.

LCDR Fred Edwards, Destroyer Type Desk, Bureau of Ships, famously said of the class, “I always felt it was the Fletcher class that won the war . . .they were the heart and soul of the small-ship Navy.”

Named in honor of Continental/Pennsylvania Navy Commodore John Hazelwood, famous for defending Philadelphia and the Delaware River against British man-o-wars in 1777 with a rag-tag assortment of gunboats and galleys, the first USS Hazelwood (Destroyer No. 107) was a Wickes-class greyhound commissioned too late for the Great War and scrapped just 11 years later to comply with naval treaty obligations.

The subject of our tale was laid down by Bethlehem Steel, San Francisco on 11 April 1942– some 79 years ago this week and just four months after Pearl Harbor. She was one of 18 built there, all with square bridges, as opposed to other yards that typically built a combination of both square and round bridge designs. Commissioned 18 June 1943, she was rushed to the pitched battles in the Western Pacific.

Aft plan view of the USS Hazelwood (DD 531) in San Francisco on 3 Sep 1943. Note her three aft 5″/38 mounts, depth charge racks, and torpedo tubes.

Forward pan view of the USS Hazelwood (DD 531) in San Francisco on 3 Sep 1943. A good view of her forward two 5″ mounts.

By October 1943, she was in a fast carrier task force raiding Wake Island.

Switching between TF 52 and TF 53, she took part in the invasion of the Gilbert Islands, Kwajalein, and Majuro Atolls in the Marshall Islands, then came the Palaus. Next came the Philippines, where she accounted for at least two kamikazes during Leyte Gulf.

In early 1945, she joined TF 38, “Slew” McCain’s fast carrier strike force for his epic Godzilla bash through the South China Sea, followed up by strikes against the Japanese home islands.

Then came Okinawa.

While clocking in on the dangerous radar picket line through intense Japanese air attacks, she became the center of a blast of divine wind.

From H-Gram 045 by RADM Samuel J. Cox, Director, NHHC:

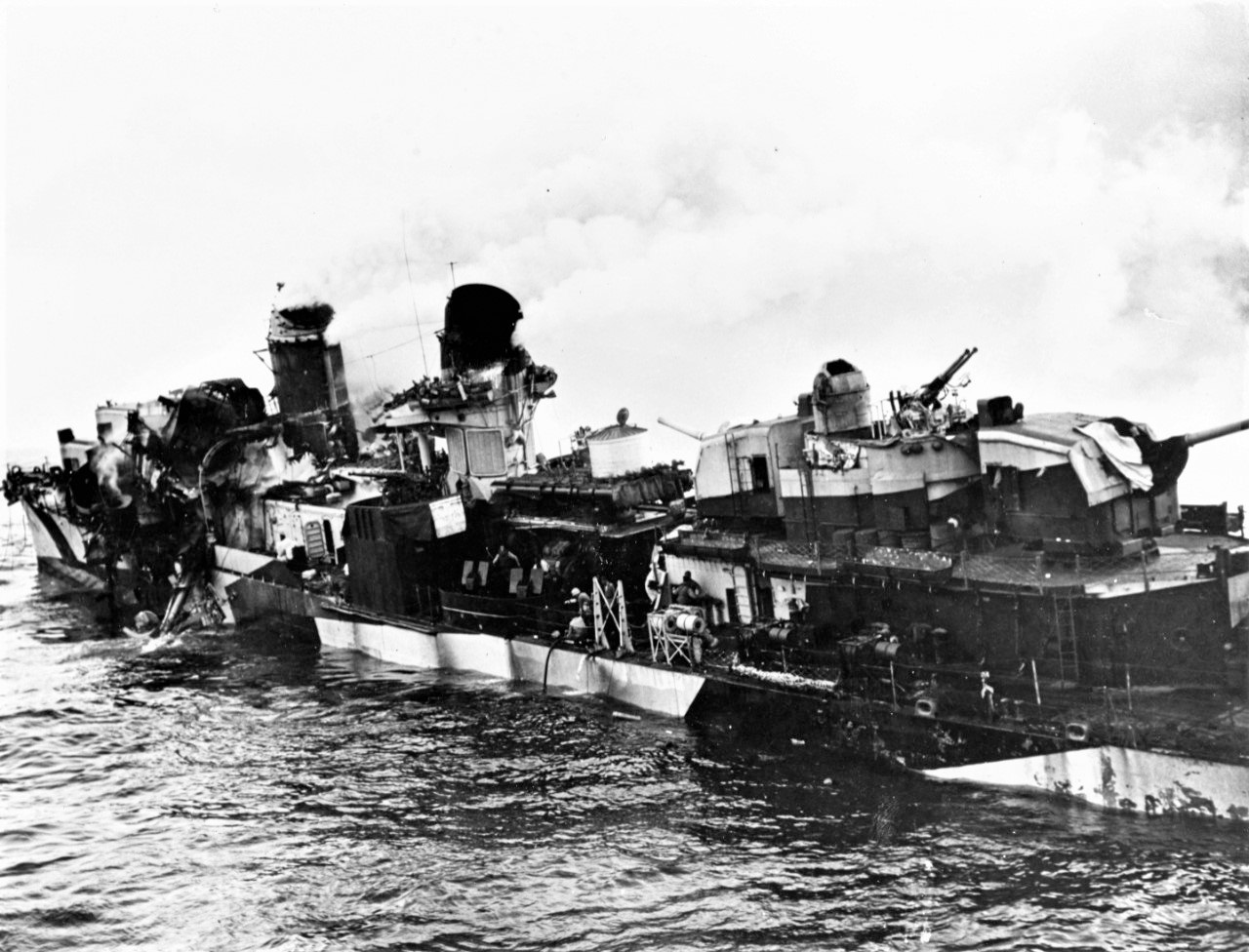

As destroyer Hazelwood was steaming to assist Haggard (DD-555) on 29 April, three Zekes dropped out of the overcast. Hazelwood shot down one, which crashed close aboard, and the other Zeke missed. The third Zeke came in from astern. Although hit multiple times, it clipped the port side of the aft stack and then crashed into the bridge from behind, toppling the mainmast, knocking out the forward guns, and spraying flaming gasoline all over the forward superstructure. Its bomb exploded, killing the commanding officer, Commander Volkert P. Douw, and many others, including Douw’s prospective relief, Lieutenant Commander Walter Hering, and the executive officer and ship’s doctor.

The engineering officer, Lieutenant (j.g.) Chester M. Locke, took command of Hazelwood and directed the crew in firefighting and care of the wounded. Twenty-five wounded men had been gathered on the forecastle when ammunition began cooking off. Because of the danger of imminent explosion, the destroyer McGowan (DD-678) could not come alongside close aboard. The wounded were put in life jackets, lowered to the water, and able-bodied men dove in and swam them to McGowan. Only one of the wounded men died in the process. Hazelwood’s crew got the fires out in about two hours and McGowan took her in tow until the next morning, when Hazelwood was able to proceed to Kerama Retto under her own power and, from there, to the West Coast for repairs. Although Morison gives a casualty count as 42 killed and 26 wounded, multiple other sources state 10 officers and 67 enlisted men were killed and 36 were wounded. Locke was awarded a Navy Cross.

“USS Hazelwood survives two suicide plane attacks. US Navy Photo 126-15.” Okinawa, Japan. April 1945

USS Hazelwood (DD-531) after being hit by a kamikaze off Okinawa, 29 April 1945. Accession #: 80-G Catalog #: 80-G-187592

USS Hazelwood (DD-531), June 16, 1945. Damaged by kamikaze on April 29, 1945. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. 80-G-323986

Notably, two of her sisterships– USS Pringle (DD-477) and USS Bush (DD-529)— had been sunk by kamikaze aircraft off Okinawa less than two weeks before the attack on Hazelwood and three more– USS Luce (DD-522), USS Little (DD-803), and USS Morrison (DD-560)— would suffer a similar fate within the week afterward. Life was not easy for Fletchers working the picket line in the Spring of 1945.

Sent to Mare Island for repairs, Hazelwood was decommissioned on 18 January 1946 and entered the Pacific Reserve Fleet at San Diego, her war over. She received 10 very hard-earned battle stars for her World War II service.

She was luckier than 19 of her sisters who were sunk during the conflict, along with five others who, like her, suffered extreme damage and somehow remained afloat but were beyond economic repair once the nation came looking for a peace dividend. This works out to a loss rate of about 14 percent for the class.

DASH

By the time the Korean War kicked off, and the Soviets were quickly achieving parity on the high seas due to a rapidly-expanding snorkel-equipped submarine arm, 39 improved square-bridge Fletchers were taken out of mothballs and, through the project SCB 74A upgrade, a sort forerunner of the 1960s FRAM program, given new ASW weapons such as Hedgehog and Weapon Alpha in place of anti-ship torpedo tubes, deleted a 5-inch mount (earning the nickname of “4-Gun Fletchers) and swapped WWII-era optically-trained 40mm and 20mm AAA guns for three twin radar-guided 3-in mounts.

The Navy had something else in mind for Hazelwood.

Recommissioned at San Diego on 12 September 1951, she was sent to the Atlantic for the first time to work up with anti-submarine hunter-killer groups while still in roughly her WWII configuration.

USS Hazelwood (DD-531) in the 1950s, still with 40mm Bofors, at least one set of torpedo tubes, and all 5 big guns. USN 1045624

By 1954, she was back in the Pacific, cruising the tense waters off Korea, which had just settled into an uneasy truce that has so far held out. Then came a series of cruises in the Med with the 6th Fleet.

Ordered to Narragansett Bay in 1958, she was placed at the disposal of the Naval Ordnance Laboratory to help develop the Navy’s planned anti-submarine drone. Produced by Gyrodyne Co. of America, Inc., of Long Island, New York, it was at first designated DSN-1.

It made the world’s first free flight of a completely unmanned drone helicopter, long before the term “UAV” was minted, at the Naval Air Test Center, Patuxent River in August 1960, and Hazelwood provided onboard testing facilities, with her stern modified for flight operations with the removal of her torpedo tubes and two 5-inch mounts and the addition of a flight deck and hangar– the first time a Fletcher carried an aircraft since the brief run of a trio of catapult-equipped variants.

“U.S. Navy’s First Helicopter Destroyer Conducts Exercises. USS Hazelwood is the Navy’s first anti-submarine helicopter destroyer, steams off the Atlantic coast near Newport, Rhode Island. Attached to Destroyer Development Group Two, Hazelwood is undergoing extensive training exercises to acquaint her crew with air operations. Her flight deck is designed to accommodate the DSN-1 Drone Helicopter (QH-50) scheduled for delivery from Gyrodyne Company of America, Inc. Soon, an HTK Drone Helicopter with a safety pilot, developed by the Kaman Aircraft Company, is being used for training exercises until the DSN-1 Drone becomes available. Through the use of drone helicopter and homing torpedo, Hazelwood will possess an anti-submarine warfare kill potential at much greater range than conventional destroyers.” The photograph was released on 1 September 1959. 428-GX-USN 710543

According to the Gyrodyne Helicopter Historical Foundation, “the DASH Weapon System consisted of the installation of a flight deck, hangar facility, deck control station, CIC control station, SRW-4 transmitter facility, and fore and aft antenna installation” and could carry a nuclear depth charge or Mk44 torpedo.

USS HAZELWOOD (DD-531) Photographed during the early 1960s while serving as “DASH” test ship. NH 79114

Anti-Submarine Demonstration during the inter-American Naval conference, 1-3 June 1960. An HS-1 Seabat helicopter uses its sonar while S2F and P2V patrol planes fly over USS DARTER (SS-576), USS CALCATERRA (DER-390), and USS HAZELWOOD (DD-531). The demonstration was witnessed by Naval leaders of 10 American nations. USN 710724

Hazelwood received two lengthy respites from her DASH work, brought about by pressing naval events of the era. The first of these was the Cuban Missile Crisis in late 1962, serving as Gun Fire Support Ship for Task Force 84 during the naval quarantine of the worker’s paradise.

The second was in April 1963 when the newly built attack boat USS Thresher (SSN-593) failed to surface. Hazelwood was one of the first ships rushed to begin a systematic search for the missing submarine, escorting the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s RV Atlantis II to the site and hosting several of the lab’s scientists and equipment aboard.

After her search for Thresher, Hazelwood returned to her job with the flying robots, completing over 1,000 sorties with DASH drones in 1963 alone and helping develop the Shipboard Landing Assist Device (SLAD). That year, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara approved budgeting for enough aircraft to provide two plus one backup aircraft for each of the Navy’s 240 FRAM-1 & 2 destroyers in addition to development models.

By 1965, DASH drones were being used for hour-long “Snoopy” missions directing naval gunfire with real-time video in Vietnam at the maximum range of the ship’s 5-inchers.

With the drone, designated QH-50, ready for fleet use, Hazelwood’s work was done. Instead of a gold watch, she got what so many of her class ended up with– disposal.

Epilogue

Hazelwood decommissioned on 19 March 1965, just as the QH-50 program was fully matured and entered the Atlantic Reserve Fleet. Stricken 1 December 1974, she was subsequently sold 14 April 1976 to Union Minerals & Alloy, New York, and broken up for scrap.

Her plans, war diaries, 1950s logbooks, and reports are digitized in the National Archives. She is remembered in maritime art.

Kamikaze attacks on USS Hazelwood (DD 531), shown battered but still afloat, April 29, 1945. Artwork by John Hamilton from his publication, “War at Sea,” pg. 256. Courtesy of the U.S. Navy Art Gallery, accession 88-66-K.

A reunion blog for her crew remained updated until 2019.

The rest of her surviving sisters were likewise widely discarded in this era by the Navy, who had long prior replaced them with Knox-class escorts. Those that had not been sent overseas as military aid was promptly sent to the breakers or disposed of in weapon tests. The class that had faced off with the last blossom of Japan’s wartime aviators helped prove the use of just about every anti-ship/tactical strike weapon used by NATO in the Cold War including Harpoon, Exocet, Sea Skua, Bullpup, Walleye, submarine-launched Tomahawk, and even at least one Sidewinder used in surface attack mode. In 1997, SEALS sank the ex-USS Stoddard (DD-566) via assorted combat-diver delivered ordnance. The final Fletcher in use around the globe, Mexico’s Cuitlahuac, ex-USS John Rodgers (DD 574), was laid up in 2001 and dismantled in 2011.

Today, four Fletchers are on public display, three of which in the U.S– USS The Sullivans (DD-537) at Buffalo, USS Kidd (DD-661) at Baton Rouge, and USS Cassin Young (DD-793) at the Boston Navy Yard. Please try to visit them if possible. Kidd, the best preserved of the trio, was used extensively for the filming of the Tom Hanks film, Greyhound.

As for the DASH, achieving IOC in late 1962, it went on to be unofficially credited as the first UAV to rescue a man in combat, carrying a Marine in Vietnam who reportedly rode its short skids away from danger and back to a destroyer waiting offshore. However, due to a lack of redundant systems, they were often lost. By June 1970, the Navy had lost or written off a staggering 411 of the original 746 QH-50C/D drone helicopters built for DASH. Retired in 1971 due to a mix of unrealized expectations, technological limitations for the era (remember, everything was slide rules and vacuum tubes then), and high-costs, OH-50s remained in military use with the Navy until 1997, soldiering on as targets and target-tows. The last operational DASH, ironically used by the Army’s PEO STRI-TMO, made its final flight on 5 May 2006, at the SHORAD site outside the White Sands Missile Range, outliving the Fletchers in usefulness.

A few are preserved in various conditions around the country, including at the Intrepid Air & Space Museum.

Ever since USS Bronstein (DE/FF-1037) was commissioned in 1963, the U.S. Navy has more often than not specifically designed their escorts to operate helicopters, be they unmanned or manned.

Specs:

Displacement 2,924 Tons (Full),

Length: 376′ 5″(oa)

Beam: 39′ 7″

Draft: 13′ 9″ (Max)

Machinery, 60,000 SHP; Westinghouse Turbines, 2 screws

Speed, 38 Knots

Range 6500 NM@ 15 Knots

Crew 273.

Armament:

5 x 5″/38 AA,

6 x 40mm Bofors

10/11 x 20mm AA

10 x 21″ tt.(2×5)

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!