Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Feb. 7, 2024: Moscow on the Hudson

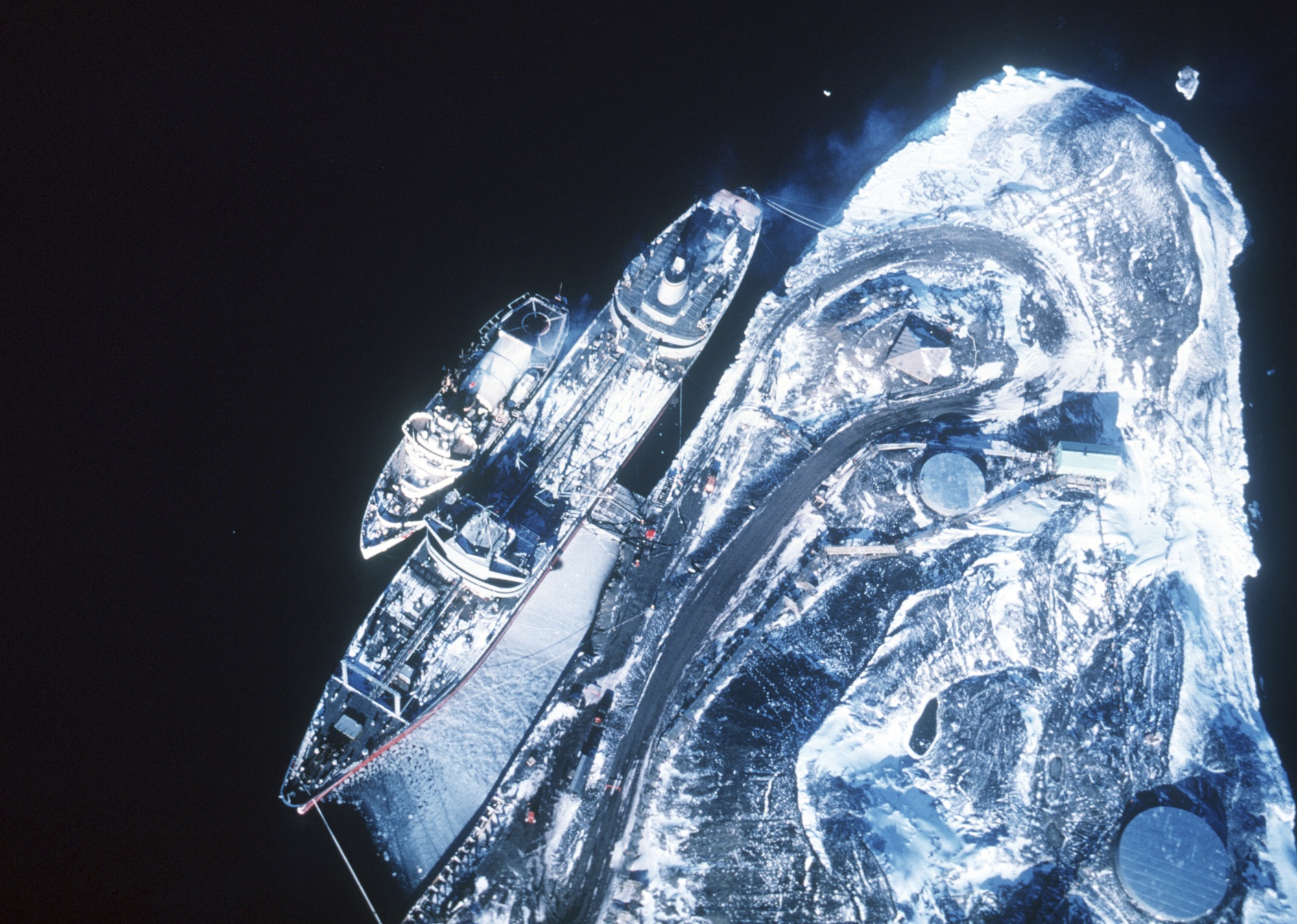

U.S. Navy Photo donated by Charlotte Koch, whose husband, Richard Koch, was a Navy P2V pilot who served in Antarctica in the 1950s, via the National Science Foundation’s U.S. Antarctic Program archives.

Above we see the well-traveled Wind-class “battle icebreaker” USS Staten Island (AGB-5) hanging out with the locals and breaking a channel into McMurdo Sound on 11 February 1959, some 65 years ago this week. Staten Island served in three different fleets across 30 years and had an interesting tale to tell.

How the “Winds” came to blow

When World War II started, the U.S. Navy was up to the proverbial frozen creek as far as icebreaking went. While some foreign powers (the Soviets) really liked the specialized ships, Uncle Sam did not share the same opinion. However, this soon changed in 1941 when the U.S., even before Pearl Harbor, accepted Greenland and Iceland to their list of protected areas. Now, tasked with having to keep the Nazis out of the frozen extreme North Atlantic/Arctic and the Japanese out of the equally chilly North Pac/Arctic region (anyone heard of the Aleutians?), the Navy needed ice-capable ships yesterday.

The old (read= broken down) 6,000-ton British-built Soviet icebreaker Krassin was studied in Bremerton Washington by the Navy and Coast Guard. Although dating back to the Tsar, she was still at the time the most powerful icebreaker in the world.

The 10,000-ton. 323-foot Russian icebreaker Krassin, seen here in the Panama Canal, was studied by the USCG stateside for several months in 1941, with her design teaching the service many lessons

After looking at this ship and the Swedish icebreaker Ymer, the U.S. began work on the Wind-class, the first U.S. ships designed and built specifically as icebreakers.

Set up with an extremely thick (over an inch and a half) steel hull, these ships could endure repeated ramming against hard-pack ice. Just in case the hull did break, there were 15 inches of cork behind it, followed by a second inner hull. Now that is serious business. These ships were so hardy that one, USCGC Westwind (WAGB 281), almost 30 years after she joined the fleet, was heavily damaged by ice in the Antarctic’s Weddell Sea but still made it back. About 120 feet of the port-side hull was gashed when brash ice forced the ship against a 100-foot sheer ice shelf. The gash was two to three feet wide and was six feet above the waterline. The crew patched the side, there were no injuries, and the breaker returned home under her own power.

At over 6,000 tons, these ships were bulky for their short, 269-foot hulls. They were also bathtub-shaped, with a 63-foot beam. For those following along at home, that’s a 1:4 length-to-beam ratio. Power came from a half-dozen mammoth Fairbanks-Morse 10-cylinder diesel engines that both gave the ship a lot of power on demand, but also an almost unmatched 32,000-mile range (not a misprint, that is 32-thousand). For an idea of how much that is, a Wind-class icebreaker could sail at an economical 11 knots from New York to Antarctica, and back, on the same load of diesel…twice.

A photo of USCGC Eastwind, circa 1944. Note how beamy these ships were. The twin 5-inch mounts on such a short hull make her seem extremely well-armed. USCG Photo

To help them break the ice, the ship had a complicated system of water ballasting, capable of moving hundreds of tons of water from one side of the ship to the other in seconds, which could rock the vessel from side to side in addition to her thick hull and powerful engines. A bow-mounted propeller helped chew up loose ice and pull the ship along if needed.

With a war being on, they just weren’t about murdering ice, but being able to take the fight to polar-bound Axis ships and weather detachments as well. For this, they were given a pair of twin 5″/38 turrets, a dozen 40mm Bofors AAA guns, a half dozen 20mm Oerlikons, as well as depth charge racks and various projectors, plus the newfangled Hedgehog device to slay U-boats and His Imperial Japanese Majesty’s I-boats. Weight and space were also reserved for a catapult-launched and crane-recovered seaplane. Space for an extensive small arms locker, to equip landing parties engaged in searching remote frozen islands and fjords for radio stations and observation posts, rounded out the design.

Two of the class, Eastwind and Southwind, operated against teams of German scientists and military personnel who attempted to establish weather stations in remote areas of Greenland late in the war.

As noted by the USCG Historian’s Office in this chapter of “The Weather War,”:

On 4 October 1944 Eastwind captured a German weather station on Little Koldewey Island and 12 German personnel. On 15 October 1944 Eastwind captured the German trawler Externsteine and took 17 prisoners. The trawler was renamed East Breeze and a prize crew sailed her to Boston.

The tender was so specific and intricate that only a single shipbuilder submitted a bid, the Western Pipe & Steel (WPS) Corporation of Los Angeles, the yard that would build all eight members of the class.

Meet Staten Island, or…well, we’ll get to it

Laid down on 9 June 1942 at WPS as Yard No. CG-96 for a contract price of $9,880,037, our icebreaker would be the first Northwind (more on that below) but that was just a placeholder as from the outset it was intended to Lend Lease this first ship of the class to the Soviets, who desperately needed it to keep the country’s chimney at Murmansk and Archangel (Arkhangelsk) open during ice season– and to repay the loan of Krassin, whose design helped influence the Winds.

As such, she shipped out without radar, some of the more sensitive commo gear that her sisters had, and a simplified armament (four 3″/50 singles, 8x40mm Bofors, 6x20mm Oerlikon, and two depth charge racks).

“Hull #96 Launching Dec. 28, 1942 – #63.”; Note her forward screw shaft under a huge overhanging bow, augmenting two shafts on her stern. Photo by “Dick” Whittington Photography, Los Angeles, CA via USCG Historian’s Office.

Hull CR96 [sic, CG96] 3/4 Bow view – San Pedro Harbor; Western Pipe & Steel Co. Shipyard. 10 February 1942. Note her two 3″/50s forward, Bofors singles under her wheelhouse windows, and magazine-less 20mm Orlikons on the roof. Also, note that she has no radar fit. Photo No. 42-69-92 by “Dick” Whittington Photography, Los Angeles, CA via USCG Historian’s Office.

Launched 28 December 1942, she commissioned 26 February 1944– 80 years ago this month– with a placeholder Coast Guard crew and USCG hull number (WAG-278) but was turned over to a waiting Russian crew almost immediately, with the Coasties only riding along as far as Seattle, which the Northwind left on 9 March headed for the Motherland with a red flag flying.

Russki Days

In total, three of the eight Wind-class icebreakers were lent to the Soviets: our Northwind (renamed Severnyy Veter= North Wind), Southwind (Admiral Makarov), and Westwind (Severnyy Polyus= North Pole).

In Soviet service, Northwind/Severnyy Veter was placed under the direction of the state-owned Arkhangelsk Arctic Shipping Company (GUSMP), based in Murmansk, but had to get there first. She was assigned to the Navy List of the list of vessels of the Main Northern Sea Route on 4 March and, leaving Seattle five days later, arrived at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on 25 March where she temporarily became part of the Vladivostok Arctic Shipping Company, spending the rest of the year escorting ships and patrolling waters in the Russian Far East before making the trip along the country’s Arctic coast– the Northern Sea Route– arriving in Arkhangelsk in December 1944.

Northwind/Severnyy Veter spent the rest of the Great Patriotic War conducting ice escorts of ships and allied convoys in the White Sea. As for her two sisters that were transferred– Southwind/Admiral Makarov and Westwind/Severnyy Polyus— they were only turned over to the Soviets in February and March 1945, respectively.

When the wartime commander of the GUSMP, Captain 1st Rank Mikhail Prokofievich Belousov, a proper Hero of the Soviet Union, passed away in 1946, Northwind/Severnyy Veter was renamed Kapitan Belousov in his honor.

Belousov, a trained polar navigator who had in the 1930s commanded the old icebreaker Krassin– which the U.S. Navy had studied before designing the Wind class– had crossed the roof of the world several times along the great Northern Sea Route, come to the rescue of the disabled icebreaker Georgy Sedov, and had supervised Soviet maritime transport in the Arctic during WWII.

Repatriation

Her time under the Red Banner over, her Soviet crew sailed Kapitan Belousov to Bremerhaven in West Germany where she was met by a party from the U.S. Navy, and the ship was unceremoniously transferred back to American custody there on 19 December 1951. As with other Allied ships returned from the Russians in this era, she was reportedly in very rough shape and filthy, no doubt done on purpose.

After six weeks of cleaning and repair at Bremerhaven, she was commissioned there as USS Northwind (AGB-5) on 31 January 1952, with CDR John Boynton Davenport, USN (USNA 1941), in command. Arriving at Boston after a slow Atlantic crossing, she needed a further four months to bring her back up to Navy standards.

USN Days

In the eight years that Northwind/Severnyy Veter was loaned to Uncle Joe and the gang, the Coast Guard had picked up a second USCGC Northwind (WAGB-282), which was commissioned in July 1945. Thus, to keep from confusing the two, the original Northwind/Severnyy Veter was renamed USS Staten Island (AGB-5) on 25 February 1952—the only Navy vessel to carry that name.

Her Russian-era armament landed, and she picked up her first 5-incher, a sole 5”/38 DP in a Mark 30 enclosed single mount, as well as an SPS-6 radar set and lots of new commo gear.

Now haze gray and underway, Staten Island‘s first Navy deployment from Boston was to Frobisher Bay, where she conducted ice reconnaissance from July through September. The next year she notably became the first Navy ship to cut through the Davis Strait from Thule Air Base to the Alert station on Ellesmere Island, just 435 miles from the North Pole.

She was a key vessel in Project Mushrat and sortied 14 Rockoons (balloon-assisted stratosphere sounding rockets) carrying instruments for the Naval Research Laboratory and Iowa State University.

An 11-foot long/200-pound Deacon sounding rocket is shown being towed by a Skyhook balloon in a combination known as “Rockoon”. It was launched from the icebreaker USS Staten Island during the Arctic expedition of 1953. The rocket was wrapped in plastic to avoid freezing at altitude. (via Stratocat)

As detailed by the Navy:

This project, known as Project Mushrat, is sponsored by the Office of Naval Research with the assistance of the Bureau of Aeronautics and the Military Sea Transportation Service – Atomic Energy Commission Joint Program of Basic Research in Nuclear Physics, and the Naval Research Laboratory Program of Upper Atmosphere Research. Because of the widespread interest in the project, and particularly in the balloon-rocket technique, several observers from the three military services will accompany the expedition. The Balloon-Rocket Technique, commonly referred to as Balloon Assisted Take-Off (BATO) or Rockoon, was developed by Dr. James A. Van Allen at Iowa State University and used on board the USCGC Eastwind during the summer of 1952. This method makes it possible to reach high altitudes by small, inexpensive rockets. During the summer of 1952, one of the balloon rocket flights launched from Eastwind and achieved a peak altitude of about 295,000 feet.

Mushrat: The U.S. Navy icebreaker USS Staten Island (AGB-5) with a group of civilian and naval scientists onboard left Boston, Massachusetts, on July 18, 1953, for the North Geomagnetic Pole. They will make a comprehensive series of high-altitude observations of the primary cosmic radiation and the pressure, temperature, and density of the atmosphere in the northern latitudes. 330-PS-6008 (USN 483600)

Mushrat: “Navy Testing Cosmic Radiation at North Geomagnetic Pole. USS Staten Island (AGB-5) is shown reflecting in the water. Photograph released June 28, 1953.” 330-PS-6008 (USN 483601)

Coverage of Staten Island and Mushrat in the December 1953 All Hands:

In all, while stationed in Boston, Staten Island conducted six ice-breaking operations in northern waters between 1952 and 15 December 1954.

She then transferred to the Pacific in May 1955 and, joining her classmate icebreakers of Service Squadron 1 at Seattle, would shift to resupplying the new Distant Early Warning (DEW) radar stations in the Arctic, a role that would endure for a decade. It was during these trips that Staten Island was used as a Rockoon platform, launching a further 26 aloft in 1955 and 14 in 1958.

Northwind, I presume? Navy icebreaker Staten Island (AGB-5)/ex-Northwind (WAGB-278) approaching sistership, USCGC Northwind (WAGB-288), off Icy Cape, Alaska. 30 July 1955. Note her 5″/38 forward and her twin Bofors on the bridge wings. She also carries LCVPs. USCG Photo No. 07-30-55 (06) via USCG Historian’s Office.

She also started clocking in on regular Operation Deep Freeze runs to Antarctica’s Byrd Station and the later McMurdo Station.

USS Staten Island (AGB-5) temporarily stalled by pressure ice in the Ross Sea, during Antarctic operations, on 9 December 1958. Note Adelie penguins in the foreground. NH 99297

The above image of USS Staten Island (AGB-5) was used as the cover for the 15 July 1959 edition of Our Navy

USS Staten Island AGB-5 in the Amundsen Sea, 21 September 1960. Note the stacked LCVPs. U.S. Navy photo via USAP

14 November 1962 Staten Island (AGB-5) follows a lead in the ice of McMurdo Sound. U.S. Navy photo via USAP

25 November 1962. Steaming past Antarctica’s only known active volcano, Mount Erebus, the Seattle-based icebreaker USS Staten Island (AGB-5) widens a channel in McMurdo Sound for trailing cargo ships en route to McMurdo Station Antarctica. U.S. Navy photo via USAP

USNS Chattahoochee off-loads fuel into drums on a sled to be towed to McMurdo Station 13 miles away. The ice breaker Staten Island (AGB-5) is the center ship. The USNS Mirfak (T-AK-271) is a cargo ship to the far left. U.S. Navy Photo

In addition to paving the way to install and resupply Arctic DEW stations and Antarctic bases, Staten Island often embarked scientists directly, such as a 1963 U. S. Antarctic Research Program expedition to the Palmer Peninsula and South Shetland Islands. The expedition, led by Dr. Waldo LaSalle Schmitt from the Smithsonian, directed the icebreaker to call at 26 remote points between 18 January and 5 March, and her botanists and biologists harvested 27,000 specimens.

The U.S. Navy icebreaker USS Staten Island (AGB-5) with a HUL-1 helicopter on board approaches the Palmer Peninsula during Antarctic operations in early 1963.

1964: Navy Icebreaker AGB-5 USS Staten Island at McMurdo Station Antarctica. Note that her 5-incher has been removed

Coast Guard Days

By agreement with the Coast Guard, our girl– and all other Navy icebreakers– was placed out of commission on 1 February 1966, struck from the Navy list, and recommissioned as USCGC Staten Island (W-AGB-278), thus starting her third life.

She was painted white and upgraded, including strengthening her flight deck and hangar to permit her to operate with the new generation of HH-52 helicopters in a telescoping hangar, and her engineering plant was upgraded. By this time, she carried an SPS-10B and SPS-53A radar set in addition to her circa 1956 SPS-6C.

Wind Class Icebreaker USCGC Staten Island pictured c1968 with Navy Sea Sprite 9021 from Guam-based HC-5.

Meanwhile, in Coast Guard service her main guns had already been removed, and she spent the rest of her career with a few machine guns (four M2 .50 cals) and her small arms locker.

Staten Island at a Navy pier with her hangar fully extended. 31 July 1967; Photographer unknown. Photo No. 073167-49 via USCG Historian’s Office.

Staten Island. 14 August 1967; Note the large ice launch on her davits and telescoping hangar. Photographer unknown. USCG Photo No. 278-081467-63 via USCG Historian’s Office.

USCGC Staten Island (WAGB-278), a United States Coast Guard Wind-class icebreaker, makes its way to McMurdo Station in this undated photo. NSF photo via USAP archives.

Staten Island ice rescue team retrieving mail drop in Bering Sea. 1 March 1969; Photo No. 2780021169-23A; photographer unknown. via USCG Historian’s Office.

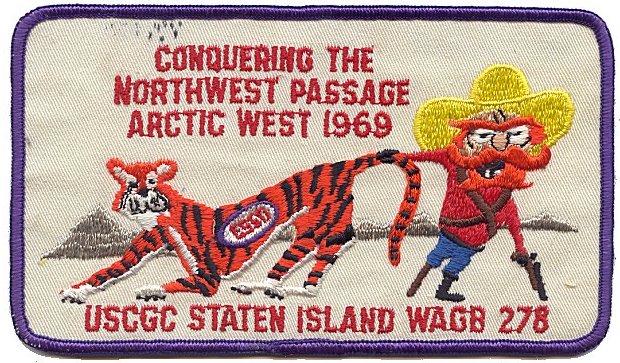

In late 1969, she navigated the Northwest Passage, escorting the Esso-chartered oil tanker SS Manhattan eastward from Seattle to New York, in concert while in Canuk waters with the smaller Canadian icebreaker Sir John A. MacDonald.

Original Kodachrome of the Staten Island (lead) and Canadian icebreaker CCGS John A. MacDonald (red hull) escort the tanker SS Manhattan (where the photographer is standing) through the Northwest Passage, September through December of 1969. Via USCG Historian’s Office

As detailed by the USCG Historian’s Office:

She rendezvoused with Manhattan and CCGS John A. MacDonald on 20 September 1969 and departed the next day. The convoy searched out heavy ice on the trip. Manhattan was testing its unique ice-breaking bow and searching for routes that merchant ships might use to transport oil from the oil fields of Alaska’s North Slope to the East Coast. By 1 October 1969, the convoy had broken through the heaviest ice in Prince of Wales Strait and Viscount Melville Sound. Staten Island assisted Manhattan “with evaluation project, photo, and ice helicopter reconnaissance, diving operations, dental treatment of Manhattan personnel and ice-breaking assistance.”

The convoy arrived in New York on 9 November 1969. On 9 December 1969, she returned to Seattle after becoming the fourth American ship in history to make the voyage around the North American continent. The others had been the cutters Storis, Bramble, and Spar in 1957. By the time she arrived back at Seattle, Staten Island had traveled 23,000 miles, stopping at New York City, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Acapulco, Mexico after transiting the Panama Canal.

When in the Arctic, she often tracked Soviet shipping, as noted by Crewman Ronald Lange, from the files of the USCG Historian’s Office of her 1970 Alaska cruise:

Our ship operated west of the Alaskan Straits to identify and track Russian merchant ships moving down towards the Straits bound mostly Vietnam. Our 2 helicopters identified ships and we were on the bridge and CIC group (I was in CIC. an RD3) documented. We identified different types of ships using mixed drinks for keywords (Martini for a freighter, whiskey sour for a tanker, etc.)…There were several Russian corvette-type escort ships and a Russian icebreaker as well. The captain of the Russian vessel came over by helicopter and saluted Captain Putzke, who was on the wing of the bridge…We were generally left alone by the Russians, except when one of our helicopters got into Russian air space near one of their early warning radar stations in the fog.

“269-ft. USCG C Staten Island (WAGB-278) masking trails through ice-paved [sic] for deliveries.”; 29 December 1970; no photo number; photo by PH3 D. H. Walker, USCG. via USCG Historian’s Office.

Deep Freeze ’71 saw Staten Island accomplish the feat of circumnavigating Antarctica, she transported a U.N. inspection mission around to the different international outposts on the continent– including the Russian bases– to ensure weapons-free treaty compliance.

U.S. Navy aerial photo of Hut Point Peninsula taken in February 1971 when the fuel tanker USNS Maumee arrived to off-load fuel (Feb 12-14). The smaller vessel to the outside is the USCGC Staten Island (WAGB-278). A careful examination of the photo will reveal the roof of British explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s 1902 Discovery Hut. The other building and fuel storage tanks have been removed since this photo was taken. Photo via USAP

13 February 1971: McMurdo Station Antarctica. Ships moored in Winter Quarters Bay. Present are USNS Maumee (T-AO-149), USNS Wyandot (T-AK-283), USCGC Staten Island (WAGB-278), and USCGC Burton Island (WAGB-283). National Archives. K-88755

Five ships in Winter Quarters Bay on 13 February 1971. In the foreground is HMNZS Endeavour (A184), across the right is USNS Wyandot (T-AKA-92) and USCGC Burton Island (WAGB-283), across the left, is USNS Maumee (T-AO-149) and USCGC Staten Island (WAGB-278). Along the shoreline, work is underway to repair and install facing an Elliott Quay – a steel-and-timber reinforcement barrier to protect the shoreline from erosion. Photo by Carl Norton, via USAP

On 9 January 1971, one of Staten Island’s embarked HH-52A Sea Guards (#1404) crashed while some 12,000 feet high into the side of Mount Erebus while on a Deep Freeze mission. The crew, uninjured, was rescued and returned to McMurdo. The helo had already suffered a near-catastrophic water landing earlier on the deployment.

As detailed by Lange:

“After the Arctic West trip of 1970, we were assigned to Operation Deepfreeze. Our ports of call on the outward leg of our trip were Hawaii. Suva, Fiji, and Wellington, New Zealand. Our air element came from Mobile, Alabama along with 2 HH-52 helos. Our trip through Fiji was uneventful, but while conducting air operations (SAR) drills, one the helos (#1404) experienced a total electrical failure at approximately 500 feet altitude and autorotated onto the ocean. No one was injured and the helo was hauled aboard with only slight damage to its hull. The copter was repaired, and electrical components were changed out on our way to McMurdo station.

We conducted ice-breaking operations along with the Burton Island in McMurdo Sound while the air element assisted ashore with cargo operations. In January 1971, while transporting base personnel around Mount Erebus, our HH-52 (#1404), experienced a severe downdraft and crashed near the summit of the mountain. It took several hours to find the aircraft as our choppers then were mostly white against a snowy background.

Staten Island also kept up her long-running knack for linking up with the Russkies.

For two weeks in February-March 1973, Staten Island met 475 miles north of Adak Island with the Soviet Far Eastern Shipping Company research vessel Priboy for a series of joint meteorological experiments in the Bering Strait. They were assisted by a NASA flying laboratory aboard an American Conveyor 990 aircraft out of Kodiak and a Soviet Il-18 operating from Cape Schmidt. The joint sea and ice study was code-named “Bering Sea Experiment” or Project BESEX, which surely inspired no shortage of Mad Magazine-level humor among all those involved.

She then spent a month (7 March to 3 April 1973) under the operational control of COMSUBPAC involved in supporting ICEX 1-73, the long-running U.S. Navy submarine exercise in the Arctic, which led to the ship earning the Coast Guard Unit Commendation with Operational Distinguishing Device. She added it to a CGUC she already picked up in 1969 for the SS Manhattan mission through the Northwest Passage and a Meritorious Unit Commendation she received in 1971 for her circumnavigation around Antarctica.

Then came, what turned out to be, Staten Island’s final Deep Freeze deployment down south.

The red-hulled USCGC Staten Island (WAGB-278) late in her career seen underway departing San Diego Bay, on 16 November 1973 after completing Fleet Readiness Training and was en route to Antarctica for Deep Freeze 74. Marine Photos and Publishing Co. canceled postcard via the NYPL collection (NYPL_b15279351-105169).

Returning to Seattle one final time, Staten Island was decommissioned on 15 November 1974 and soon afterward sold for scrap.

In all, she had counted no less than 22 skippers– 6 Soviet, 10 USN, and 6 USCG– across her 30 years of service.

Further, as far as I can tell, she was the only ship to pull off the polar hattrick of navigating the Northern Sea Route over the top of Asia and Europe (1944), the Northwest Passage over the top of North America (1969) and circumnavigating the continent of Antarctica (1971).

From patrolling for U-boats at Murmansk to supplying Byrd Station and launching Rocktoons into the stratosphere, if it was cold, Northwind I/Severnyy Veter/Station Island got it done.

Epilogue

Her plans and a few logbooks from her time as a Navy icebreaker have been digitized in the National Archives.

Meanwhile, hundreds of preserved scientific specimens in the Smithsonian’s collection were gathered along the Palmer Peninsula and South Shetland in 1963 by the USARP Expedition working from Staten Island’s decks.

HH-52 Sea Guard #1404, lost by Staten Island in 1971, remains on Mt. Erebus and is often visited by NSF staff.

A second Sea Guard from Staten Island is one of the few of the type that is preserved and on display, donated to Seattle’s Museum of Flight in 1988 and put on display in its standard livery in 2011.

The Russians still remember her as well. A detailed scale model of Northwind/Severnyy Veter is in a place of honor at the Museum of the Murmansk Shipping Company, the successor to GUSMP.

While the Navy has not commissioned another Staten Island, the Coast Guard perpetuated the name in the 45th 110-foot Island-class patrol cutter, WPB 1345, which joined the fleet in 2000.

21 October 1999. U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Staten Island (WPB 1345) is underway from Washington, DC. The cutter is returning to its homeport in North Carolina. USCG photo by PA3 Bridget Hieronymus.

She served until 2014 and was transferred to the former Russian Republic of Georgia, where she currently patrols the Black Sea as Ochamchire (P 23)-– where she will no doubt continue to cause heartburn to the Russians for years to come.

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I am a member, so should you be!