Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Feb. 21, 2024: One Unlucky Beauty

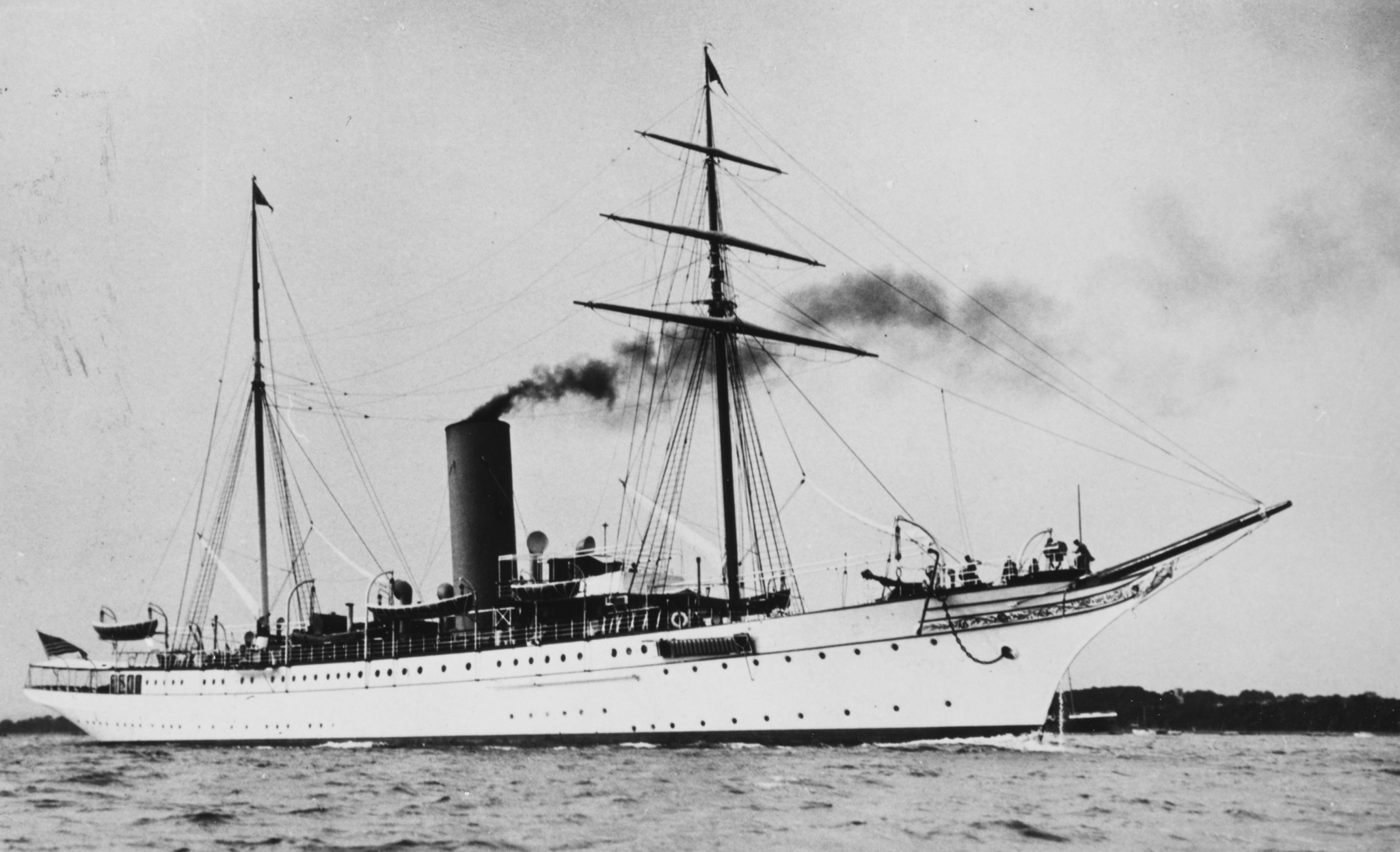

National Archives Record Group 19-LCM. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Catalog #: NH 102049

Above we see the beautiful U.S. steam yacht Nahma in all her pre-Great War finery. She had entertained Kaisers and Kings and had a strange yet underreported knack for damaging Italian warships in both times of peace and conflict.

Matching yachts for matching brothers

Ordered as Yard No. 300 from the Clydebank Engineering & Shipbuilding Co. Ltd., the fine Scottish-built Nahma was paid for in 1896 by one Mr. Robert W Goelet, son of Manhattan real estate tycoon Robert R. Goelet. A familiar design to the builder– one by George L. Watson of Glasgow– Nahma was a carbon copy of much more famous future presidential yacht Mayflower, ordered the year prior by Ogden Goelet, brother to Robert W.

As noted by the NYT in October 1897:

She is built entirely of steel, on the spar-deck principle, and has a clipper stem and a square stern. From the foremast to within 50 feet of the taffrail extends the promenade, or boat, deck, which has a length of 190 feet. The vessel is schooner rigged, each mast being in one length. She has a standing bowsprit, and in all respects her rig is most smart in appearance. She is painted white, with a green boot top, and, with her great array of portholes, her fine set of boats, including a steam launch, and her large funnels, ventilators, and awning supports, which are of metal tubes, she presents a handsome appearance.

She is subdivided into several water-tight compartments by seven bulkheads, all of which are cemented. Her dimensions are as follows:- Length on load water line, 275 feet; length between perpendiculars, 288.8 feet; and from over the figurehead to taffrail 320 feet; breadth 36.7 feet, with a depth molded of 17.7 feet. Her tonnage is 969.79 and 1,739.83, net and gross, respectively, and 1,844, according to the Thames yacht measurement.

The Nahma is equipped with electric lighting, heating, and ventilating devices, and a refrigerating machine. She is propelled by two triple expansion engines of 4,250 horsepower. On her trial trip she developed a sustained speed of 16¾ knots per hour. The yacht mounts two Hotchkiss quick-firing guns and carries a stand of carbines, and among her crew of seventy-two men is a gunner. She is commanded by Capt. Churchill, who was formerly in the Cunard service.

Yes, you read that right. As a 320-foot private yacht, she was built with a well-stocked small arms locker and carried a pair of 6-pounder QF 37mm Hotchkiss guns. More on this later.

Before the lights went out in Europe

She would sail briefly for the Winter 1897 season to the waters off New York and Newport, and early 1898 would see the new yacht back in Scottish waters for upgrades deemed needed by her owner. She was still in her builder’s yard when her sister, Mayflower, was purchased by the Navy from the estate of the late Ogden Goelet– who had passed aboard her at Cowes– and converted for use in the Spanish American War as a patrol yacht.

Speaking of the late Mr. Ogden, Robert W. Goelet passed away shortly after his brother, having only enjoyed his new yacht for a few months. He passed aboard her while in Nice in April 1899, and his body was returned to the States aboard her, the yacht’s flag at half mast, to be buried in Newport’s Woodlawn Cemetery.

While his widow, Mrs. Henrietta Louise (née Warren) Goelet, briefly considered the sale of the Nahma to Sir Thomas Lipton for £80,000, she elected instead to keep the vessel and made it her more or less permanent home for the next 13 years.

Mrs. Goelet kept Nahma underway, sailing from New England to Europe and back, where the elegant yacht was a staple of Cannes, Nice, Cowes, St. Petersburg, Christiania, and Kiel. Kaiser Wilhelm and his wife became regular guests aboard, calling on Mrs. Goelet on no less than seven occasions over the years. She also entertained King Edward and a legion of lesser nobility and both Mrs. Goelet and her skipper often received foreign orders and decorations in return.

The vessel would typically just return to American waters for the late summer cup races off New York.

American-owned yacht Nahma. Commanded by Captain George Harvey of Wivenhoe with a Colne crew of 70. She could steam at 18 kts and carried quick-firing guns and searchlights for her voyaging in remote seas. A postcard, posted in Le Havre to Mrs. S Cranfield. Mersea Museum Collection BOXL_026_004_002. Used in The Northseamen, page 185

Steam yacht Nahma. A postcard was posted to Le Havre on 20 May 1912. Date: 20 May 1912. Image: John Leather Collection. Mersea Island Museum BOXL_026_004_003

Steam Yacht Nahma at anchor. Photo from J. Gelser, Alger. John Leather Collection. Mersea Museum Collection. ID BF69_006_013

Steam Yacht Nahma at Saint Malo. Postcard. John Leather Collection. Mersea Museum Collection. BF69_006_012

On one occasion, Nahma would run afoul due to her 6-pounders while passing to Constantinople.

From the NYT:

On April 27 [1903] Mrs. Goelet with a party of New York friends entered the Dardanelles on her yacht Nahma. The Nahma carries two six-pounders mounted forward and aft, “for saluting purposes.” When the sentinels on the Turkish fortresses caught the outlines of these guns under their tarpaulin coverings there was a rushing to and fro, signals flashed back and forth, and soon a shot plunged across the Nahma’s bow and the yacht hove to.

Mrs. Goelet had a dinner engagement in Constantinople for which she had already broken all speed ordinances and she did not like interference by Turkish officers with her plans.

The officers were polite, but firm. The Nahma was a warship, witness the six-pounders, and to such the passage was closed. Two days of delay followed. Mrs. Goelet demanded that Minister Leishman secure from the Sultan respect and proper reparation for her broken dinner engagement and a passage for the Nahma.

Although an extensively married man, Abdul Hamid is not without a sense of humor. At any rate, the Nahma, six-pounders and all, was allowed to steam on at the end of two days as a yacht and not as a warship. His Sultanic Majesty also conferred on Mrs. Goelet the Grand Cordon of the Turkish Order of the Chefakat, which was not much, after all, for a woman who had done what the powers have never been able to do with all their armaments.”

She also had a crack up with the Italian Navy, suffering a collision with the elderly (and quite immobile) ironclad Affondatore in Venice in May 1906, which had been largely laid up as a guard ship there for years. With the captain of the Nahma blamed by the Italian Admiralty, Mrs. Goelet quickly offered to pay for the damages stemming from the bloodless incident.

Italian ironclad “Affondatore” in her post-1888/1889 refit configuration. The Battle of Lissa veteran was semi-retired when Nahma brushed against her in Venice in 1906. She ended her days as a floating ammunition depot at Taranto in the 1920s.

Then, in August 1912, ailing with cancer, Mrs. Goelet went to Paris for treatment there and passed in the City of Lights that December. The Nahma passed to her only son, Robert Walton Goelet, who showed little interest in the vessel, although did bring legal action to keep from having to pay an exorbitant amount of tax on the ship.

Soon, the stately ship ended up in pier-side storage in Greenock, Scotland.

War!

With the U.S. entry into the Great War, and sister Mayflower still in service with the Navy since 1898, it was an easy decision that the U.S. Navy acquire the mothballed Nahma for the duration.

Picked up in early June for the patriotic sum of $1 per year, SECNAV “Cup of Joe” Daniels wrote VADM Sims that the ship would be placed at his disposal and a battery sent from the States to arm her while a crew of 130 assorted bluejackets sent across the Atlantic aboard the steamer SS New York to man her. Meanwhile, much of her original equipment was stripped and put into dockside storage in Glasgow. Her pennant was SP 771.

She was soon after equipped with two 5″/51 mounts, two 3″/50 mounts, and two machine guns– all drawn from USS Melville (AD-2), as well as a supply of depth charges (she would later pick up two Y-guns) and placed in commission under the command of LCDR Ernest Friedrick, (USNA 1903) on 27 August. Friedrick, who had sailed on the destroyers Lawrence, Stewart, and Hopkins as well as the battleship Arkansas, had earned his sea legs with the Great White Fleet and was well-respected.

Manning a 5-inch gun on the USS Nahma. Copied from the U.S. Navy in the World War, Official pictures. Page 99. NH 124132

She would be inspected by no less a personage than King George V who had a habit of visiting American warships large and small in UK ports in 1917-18 and was no doubt familiar with Nahma.

King George V and Commander E. Friedrick of the US Navy on board the American armed yacht USS Nahma, in Liverpool, September 1917.

THE US NAVY IN BRITAIN, 1917-1918 (Q 54806) King George V and Commander E. Friedrick of the US Navy on board the American armed yacht USS Nahma, probably in Liverpool, September 1917. Copyright: � IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205287785

Then everything went bad.

The Second Italian Affair

While DANFS is short on her subsequent service, saying only:

Soon after fitting out and shakedown, Nahma reported to Gibraltar to join a group of U.S. vessels based there and serving as convoy escorts. With these ships, she escorted vessels in the Mediterranean, as well as between the U.K. and Gibraltar until the end of World War I.

Nahma was involved in a serious incident, again with the Italian fleet, just a month before the Armistice.

As described in a December 1934 article in Proceedings by LCDR Leonard Doughty:

On October 5, 1918, the Italian submarines 11-6 and 11-8, escorting the S.S. Bologna was approaching Gibraltar, coming from Bermuda. The convoy was five days late. There had been three submarines in company but one had become separated from the convoy in a fog, after sighting a supposed enemy submarine.

On the same date the U.S.S. Nahma, an armed yacht, was on patrol west of Gibraltar, and at 7:00 p.m. received a radio report of an enemy submarine in the vicinity. She proceeded toward the position given, and at 2:00 a.m., October 6, sighted a flash ahead, which resembled gunfire. At 2:30 a.m. the Bologna was sighted, followed by the two submarines.

On the Nahma, it was assumed that they were enemy submarines attacking the ship. Two shots, which did not hit, were fired at the leading submarine and the recognition signal challenge was made. After some delay, and after two more shots were fired, the correct answer was made to the challenge by the leading submarine.

The Nahma then approached the other submarine, the 11-6. As the yacht approached, men were seen running aft. They were going to hoist the colors, but on the Nahma, it was supposed that they were going to man the gun. One shot was fired, which hit the conning tower, killed two men, and wounded seven, of whom two died later. By this time the Nahma was convinced that the submarines were not enemy and stood by for the remainder of the night.

At about 5:00 A.M. the British torpedo boat 93 approached the scene and accidentally fired one shot toward the Nahma, which headed toward the flash but did not find the firing vessel. At 5:20 the T. B. 93 was observed and mistaken for another submarine, and two shots were fired at her by the Nahma before she was recognized.

In the morning, the Nahma escorted the submarines to Gibraltar.

As recalled by GM2c Lewis Clark, who was aboard that day:

On one of those submarine patrols, when we were off the coast of Spain, we spotted distant lights to starboard shortly after midnight. We steamed over to investigate and discovered a large vessel surrounded by submarines. We had no knowledge of friendly submarines in those waters, as we should have had were there any there, and it had been rumored that the Spanish were secretly supplying German submarines off the coast. It was only natural, therefore, for our captain to assume that we had come upon such an operation.

General Quarters was sounded, which meant that every man went to his battle station – I was sight center on the 3-inch gun on the quarter deck aft – full speed ahead was signaled, which, for us, was 22 knots, and the “recognition signal” was flashed from our bridge. Recognition signals were used to identify friendly craft. They were changed each midnight. We received a wrong recognition signal and reply, and the captain immediately gave the order to commence firing. We had the submarines in our gun sights when the order was given, and we were firing almost at point-blank range. Before it was discovered that the vessels were not German, we had blown the conning tower off one of the submarines, and did much damage to the others, and there were men in the water screaming for help.

It developed later that we had encountered five submarines and their mothership which the United States had given to Italy, and which were being taken by their Italian crews to Italy for service in the Mediterranean. There was hell to pay later in Gibraltar.

Friedrick was relieved and replaced by LCDR Harold Raynsford Stark of Sim’s staff, who had served briefly on sistership Mayflower, and would command the yacht over Halloween.

Sims would write the SECNAV on 17 October:

As a result of a Board of Investigation made up of officers of our own Service and the British and Italian Services, the Commanding Officer of the Nahma will be tried by General Court Martial.

Incidents of this character have occurred a number of times during the war. As previously reported, British Patrol Vessels have frequently fired on their own submarines. In one case, covered by report submitted to the Department, a British destroyer attacked, and had every reason to believe that they had destroyed a submarine, which later proved to be a British submarine which succeeded in reaching port. During the summer, a British Auxiliary Cruiser sank a French armed sailing ship owing to a misunderstanding of an attempted recognition signal.

The Commanding Officer of the Nahma is known to be a very conscientious and capable young officer, and if any fault is to be ascribed to him it was probably due more to inexperience in this particular kind of warfare than anything else. It is considered that in view of the international character of the incident, a General Court Martial is probably the best step that could be taken.

Back in the war

Nahma, placed under the command of CDR Richard Philip McCullough, (USNA 1904), the former skipper of the armed yacht USS Cythera (SP 575), was dispatched to Constantinople with a relief crew for the armed yacht USS Scorpion (PY-3), arriving there on 16 December 1918, and would later carry RADM Mark L. Bristol to Beirut and Gibraltar and State Department consulate officers to Odessa.

As noted by DANFS:

Following the Armistice, Nahma remained in the Mediterranean for relief and quasi-diplomatic work. Operating in the Aegean and Black Seas she carried relief supplies to refugee areas; evacuated American nationals, non-combatants, the sick, and the wounded from civil war-torn areas of Russia and Turkey; and provided communications services between ports.

Nahma was decommissioned on 19 July 1919 and turned back over to Mr. Goelet’s agent in Glasgow.

Part of the lost generation

Post-war, the once immaculate yacht became a bootlegger, renamed Istar. Sold to Jeremiah Brown & Co Ltd, she made at least seven voyages (the first six profitable) from Glasgow to the waters off Long Island under the employ of the colorful Sir Brodrick C. D. A. Hartwell, “The Commodore of Rum Row,” crammed with Scotch on west-bound trips.

By 1927, with Hartwell bankrupt and squeezed out of the market, Istar had been converted for service as a shark-skinning vessel working the South African and Australian coasts but this was short-lived. Having gone aground at St Augustine Bay, Madagascar, she was salvaged and scuttled off Durban in March 1931.

Epilogue

While little remains of Nahma, her sister Mayflower served as a presidential yacht until 1929 then was ordered sold by President Hoover as an economic measure, and subsequently damaged by fire while tied up at the Philadelphia Navy Yard 24 January 1931.

USS Mayflower (PY- 1) off Swampscott, Mass., circa 1919-20. At left is a navy F-5L seaplane that had been placed at the president’s disposal by the Navy Dept. NH 46443

Nonetheless, she was still around on the East Coast when World War II came, and she was acquired by the Coast Guard as a gunboat (WPE‑183) and used in ASW patrols and training duties until decommissioned a second time in July 1946. She ended her days carrying Jewish refugees to Haifa in the late 1940s. Placed on the Israeli Navy’s list as the training ship INS Maoz (K 24), she was only scrapped in 1955.

As for Nahma’s trio of Navy skippers, LCDR Fredrick Ernest was no worse for wear. Cleared by a board of inquiry for the Italian submarine incident, he went on command of the NYC Navy Yard, the destroyer USS Preble (DD-345), the collier USS Jason (AC-12), and the training ship USS Utah (AG-16). He retired from the Navy after 30 years as a captain and, passing in San Diego in 1970 at age 88, is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery.

LCDR Harold Raynsford “Betty” Stark, who commanded Nahma briefly over Halloween 1918, would become the 8th Chief of Naval Operations and supervise United States Naval Forces Europe during WWII. Retiring in 1946, he passed away in 1972 and was buried at Arlington.

Finally, her last skipper, CDR Richard Philip McCullough, retired as a rear admiral in 1932 after 27 years of service but was then recalled for WWII, serving as director of naval intelligence for the 12th District in San Francisco (1939-43) and on the planning board and intelligence panel for the Overseas branch Office of War Information (1943-45). He passed in 1960.

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!