Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday (On a Thursday) April 18, 2024: Return for the Taxpayer

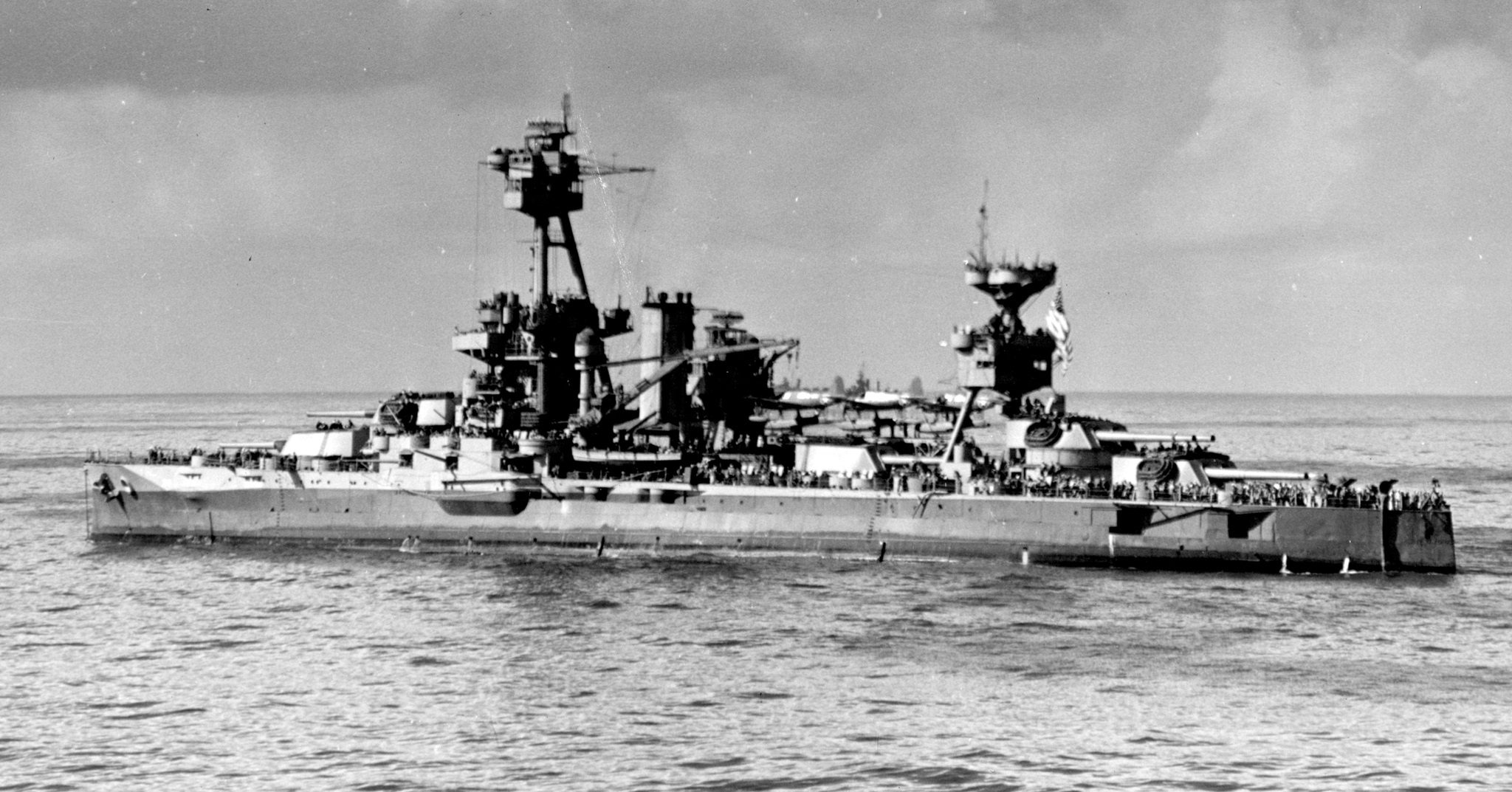

Above we see the leader of her class of dreadnoughts, USS New York (Battleship No. 34), photographed clad in Measure 31a/8B camo, off Norfolk on 14 November 1944. Note rows of shielded 20mm Orelikons manning her rails, a stern quad 40mm Bofors, and large SG and SK radars on her foremast.

Still echoing the fine lines of a Great War battlewagon– during which she served with the British Grand Fleet– New York had already done hard work in WWII off North Africa and in riding shotgun on convoys in case Kriegsmarine surface raiders appeared and is shown above just as she was preparing to leave for more fighting in the Pacific, in all steaming some 123,867 miles from 7 December 1941 to her homeward bound journey back to the East Coast from Pearl Harbor.

Commissioned on Tax Day some 110 years ago this week– 15 April 1914– for $14 million, the taxpayers got a great return for their investment.

Empire State and Lone Star

By 1911, the U.S. had ordered eight dreadnoughts in successively larger sizes in four different pairs ranging from the two-ship South Carolina class (16,000 tons, 8×12 inch guns, 18.5 knots, 12-inch armor belt), to the two-ship Delaware class (20,000 tons, 10×12 inch guns, 21 knots, 11-inch belt), the two ship Florida class (21,000 tons, 10×12 inch guns, 21 knots, 11 inch belt) and finally the two Wyoming class ships (26,000 tons, 12×12 inch guns, 20 knots, 11-inch belt).

With the lessons learned from these, the next pair, New York, and sistership USS Texas (BB-35),

Postcard showing ship information of the New York class battleships, which included USS New York (BB 34) and USS Texas (BB 35). PR-06-CN-454-C6-F6-31

The ship’s main battery would be 10 of the new 14″/45 Mark 1 guns, arranged in five two-gun turrets. It could fire a 1,400-pound Mark 8 AP shell to 22,000 yards. At point blank (6,000 yards) range, the Mark 8 was thought capable of penetrating 17.2 inches of side armor plate.

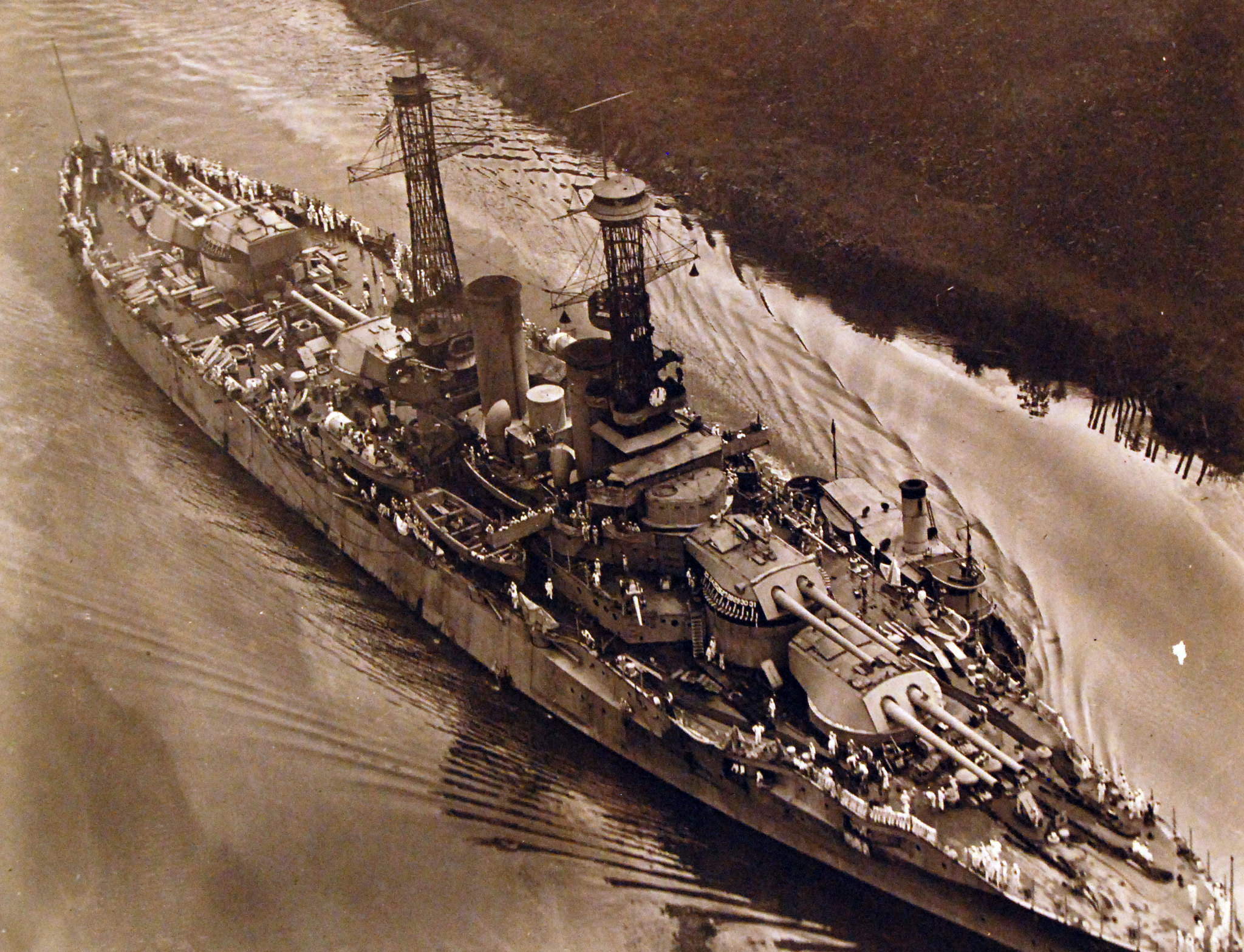

USS New York (BB-34) in her original configuration as seen from a kite balloon about 1300 feet above the ship, which was making 17 knots, giving a great overhead look at her armament. NH 45149

The secondary battery would be 21 5″/51s arranged one “stinger” aft, in casemates, and on deck. By tradition, one of these was manned by her Marine Detachment.

The class was also built, as most battleships of the era, with surface attack torpedo tubes for some reason. They had four 21-inch tubes installed- one on each side of the bow and one on each side of the stern– with co-located magazines able to carry a total of a dozen 1,500-pound Bliss-Leavitt Mark 3 torpedoes, rated to carry their 200-pound warhead to some 4,000 yards at 26 knots.

Almost as an afterthought, two 1-pounder 37mm guns were fitted, one atop each lattice mast, for AAA/counter-kite work.

Meet New York

Our subject is the fifth U.S. Navy ship to carry the moniker of the 11th State of the Union, with previous name carriers including a Revolutionary War gundalow, a 36-gun frigate burned by the Brits in 1814, a 74-gun ship-of-the-line that languished on the ways for 40 years, a screw sloop that shared a similar fate, and an armored cruiser who saw combat in the Spanish American War then was renamed (first Saratoga, then Rochester) to free up the name for new battlewagon.

“Bombardment of Matanzas” by the armored cruiser USS New York, the protected cruiser USS Cincinnati and monitor USS Puritan, April 27, 1898, by Henry Reuterdahl NH 71838-KN

The latter armored cruiser even gave up her 670-pound circa 1893 Meneely Bell Co. of Watervliet, NY, bell, which was rededicated and presented to the new New York in 1914.

Appropriately, while Texas was built at Newport News, our subject was ordered from the New York Navy Yard. The future USS New York was laid down (ironically now) on 11 September 1911 and launched on 30 October 1912, sponsored by Miss Elsie Calder, daughter of Congressman William M. Calder of Brooklyn.

She was commissioned on 15 April 1914 with her first skipper being Capt. Thomas Slidell Rodgers (USNA 1878), a veteran of the Spanish-American War.

USS New York (BB-34) the National Ensign is raised at the battleship’s stern during her commissioning ceremonies, on 15 April 1914, at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y. with a view of the same event from a different angle showing her stern 5″/51 gun mount and sistership USS Texas (BB-35) in background, fitting out with scaffolding around her main mast. NH 83711 and NH 82137.

How about this for a dreadnought shot? USS New York (BB-34) loading stores at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on April 24, 1914. Note the brown hoist 15-ton locomotive crane at left and horse-drawn vehicles, including one from the Busch Bottling Co. George G. Bain Collection. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Shortly after bringing her into commission, Rodgers took on funds for the fleet and an oversized detachment of Marines and took New York south to the Gulf of Mexico, where the brand-new battleship served as the flagship for RADM Frank Friday Fletcher’s squadron blockading Veracruz, Mexico, a role she continued to hold through most of the summer.

USS New York (BB-34) underway at high speed, 29 May 1915. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives. 19-N-13046

After the crisis abated, New York would sail for Hampton Roads and assume the mantle of flagship, First Division, Atlantic Fleet, which she would hold until March 1915. She would then spend the next two years in an annual cycle of winter gunnery and tactical training in Caribbean waters and summer cruising off the East Coast.

USS New York (BB-34). In Hampton Roads, Virginia, 10 December 1916. Note the rangefingers atop Turrets No. 2. and No. 4. NH 45138.

War!

When the Great War finally reached the long-slumbering American giant in April 1917, New York and her sisters began a feverish workup period to get war-ready. For what, it turned out, was to be tapped to augment the British fleet. As the newest U.S. battleships were oil burners, and New York– at the time, the flagship of Division Six, Atlantic Fleet– and her older sisters and cousins could still be fed on good Welsh coal, the call went through.

As detailed by DANFS:

The Navy Department, on 12 November 1917, selected the coal-burners New York, Florida (Battleship No. 30), Wyoming, and Delaware (Battleship No. 28) to form Battleship Division Nine as reinforcement for the British Grand Fleet. The battleships were to be commanded by Rear Adm. Hugh Rodman. The next day the flag for Division Six, Battleship Force was transferred from New York to Utah (Battleship No. 31) and the flag for the Commander of Division Nine, Battleship Force was broken in New York. The battleship arrived at Tompkinsville on 15 November and the next day, she shifted to the New York Navy Yard to be fitted out for distant service. She remained at the yard until the 22nd, when she departed for Lynnhaven Roads, Va., arriving on the 23rd.

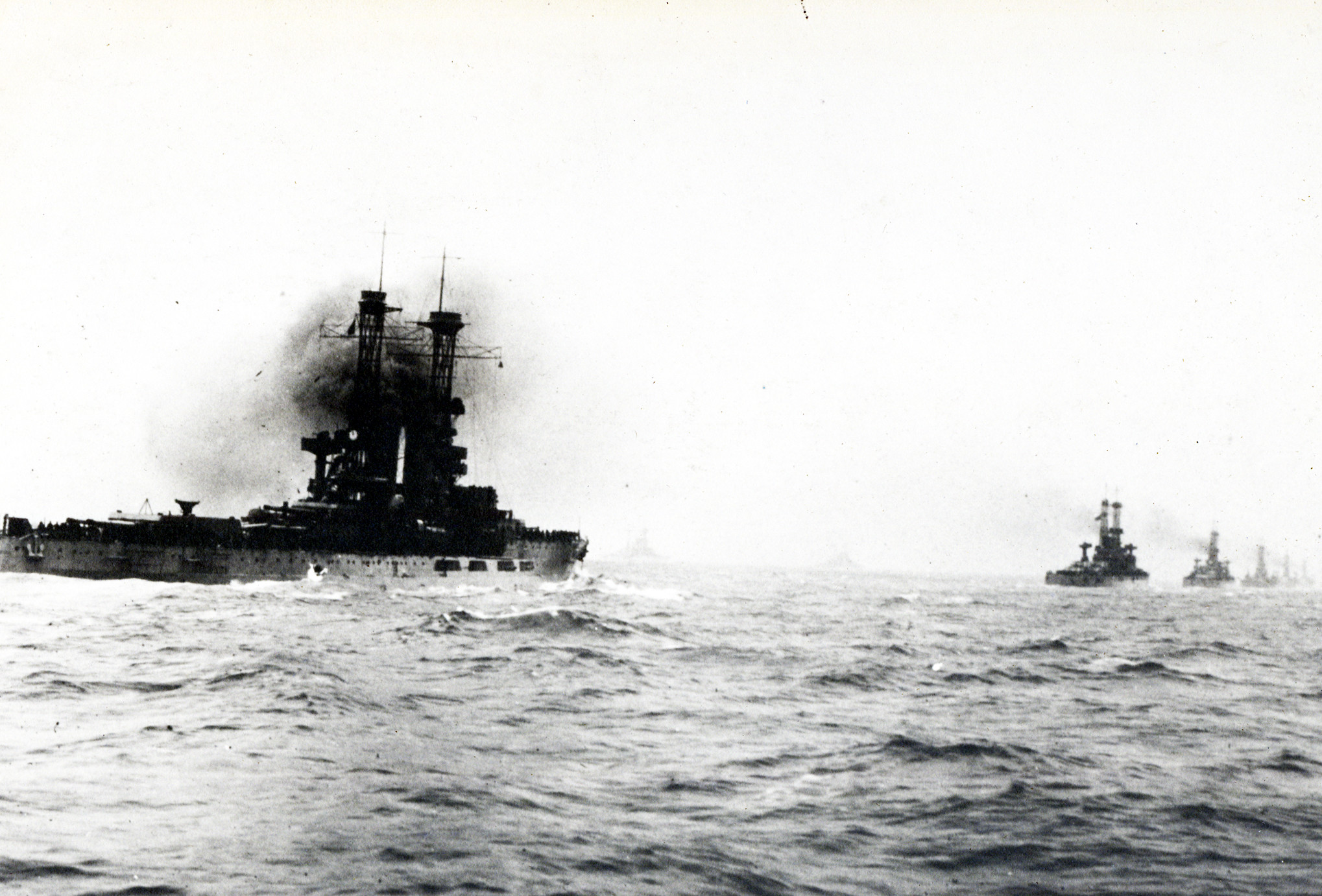

At 3:00 p.m. on 25 November 1917, Battleship Division Nine sailed from Lynnhaven Roads with Manley (Destroyer No. 74) in escort. While Manley was to join the convoy escort and patrol forces based at Base No. 6, Queenstown [Cobh], Ireland, Division Nine was bound for the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet anchorage at Scapa Flow, Orkney Islands, Scotland, to serve under the command of Adm. Sir David Beatty, RN. The weather on the voyage was bad from the start, but worsened during the night of 30 November-1 December. Delaware and Florida lost contact with New York and Wyoming. New York took on over 250 tons of water in her chain locker and forward compartments and only the efforts of bailing lines for three days prevented the ship from foundering. Division Nine eventually re-consolidated at 7:00 a.m. on 7 December at Cape Wrath and continued on to Scapa Flow. With a hearty welcome from the crews of the ships of the Grand Fleet, the ships anchored at noon.

“Arrival of the American Fleet at Scapa Flow, 7 December 1917” Oil on canvas by Bernard F. Gribble, depicting the U.S. Navy’s Battleship Division Nine being greeted by British Admiral David Beatty and the crew of HMS Queen Elizabeth. Ships of the American column are (from front) USS New York (BB-34), USS Wyoming (BB-32), USS Florida (BB-30) and USS Delaware (BB-28). U.S. Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C. NH 58841-KN

Under British command, Battleship Division Nine was re-designated as the Sixth Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet.

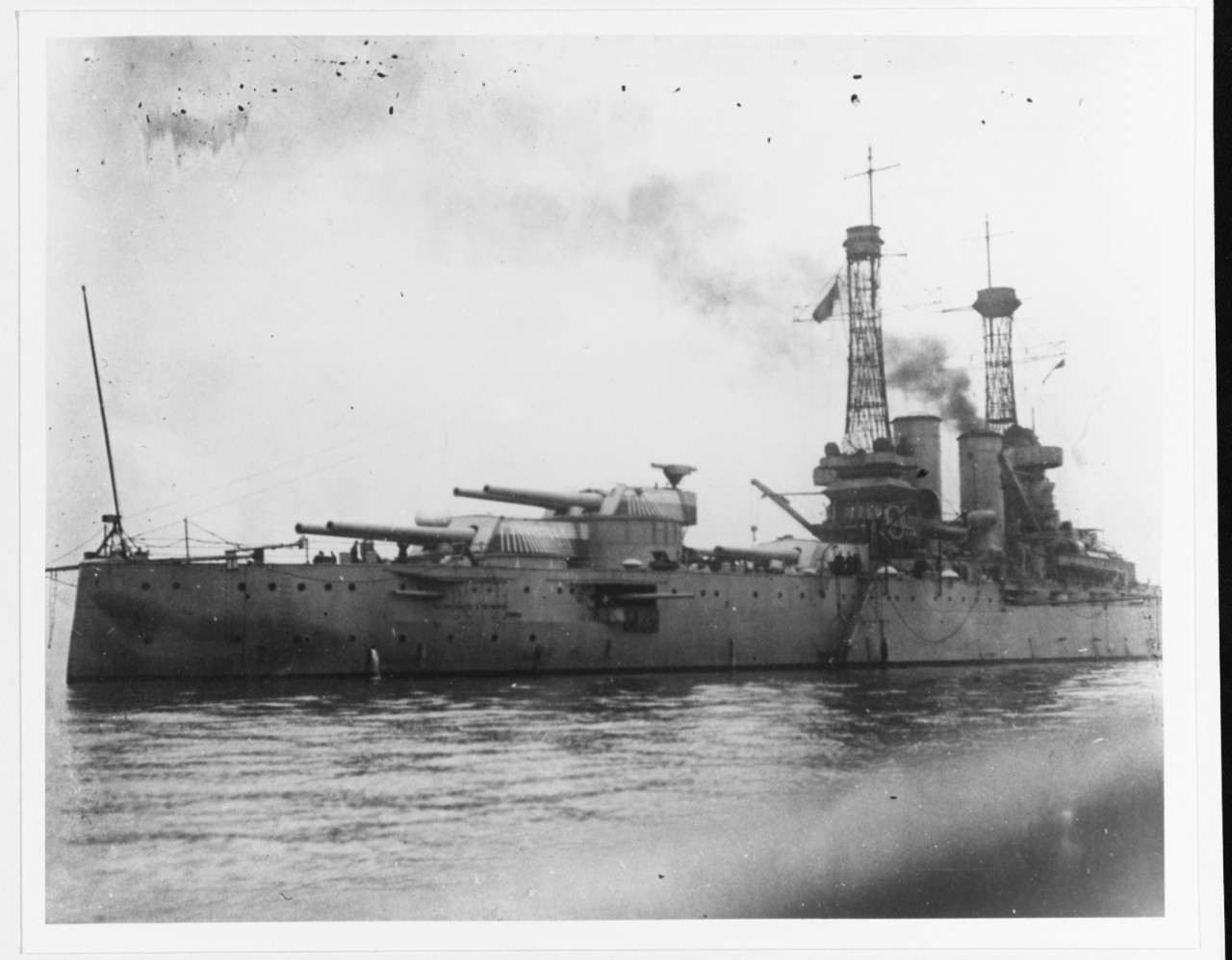

USS New York (BB-34) camouflaged with a false bow, in 1917-18, while serving in British waters. Note another American battlewagon in the background left. NH 45142

The Squadron sailed extensively on both workups with the British and convoy missions, with New York’s gun crews counting at least one encounter with a German U-boat.

When the Germans finally sortied out in strength, it was to surrender.

New York, with VADM William Snowden Sims and RADM Hugh Rodman aboard, assumed her position in column with the entirety of the Grand Fleet in the Firth of Forth on 21 November 1918, to accept the surrender of the High Seas Fleet.

Surrender of German High Seas Fleet, as seen from USS New York, 21 November 1918. Oil on canvas by Bernard F. Gribble, 1920. NH 58842-KN

Battleships of the Sixth Battle Squadron The squadron is shown anchored in a column in the left half of the photograph, at Brest, France, on 13 December 1918. NH 109382.

While seconded to the Royal Navy, New York played host repeatedly to visiting royals in British waters. This included Admiral Price Hirohito (yes, the future Emperor, on his only visit to an American warship), King George V, the young Prince of Wales (future King Edward VIII) King Albert of Belgium, the 8th Duke and Dutchess of Athol, and Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn.

She would also escort Wilson to France for the Versailles conferences.

USS New York (Battleship #34) escorted President Wilson to France in 1918. Note the AAA guns on platforms between the stacks. Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 48144

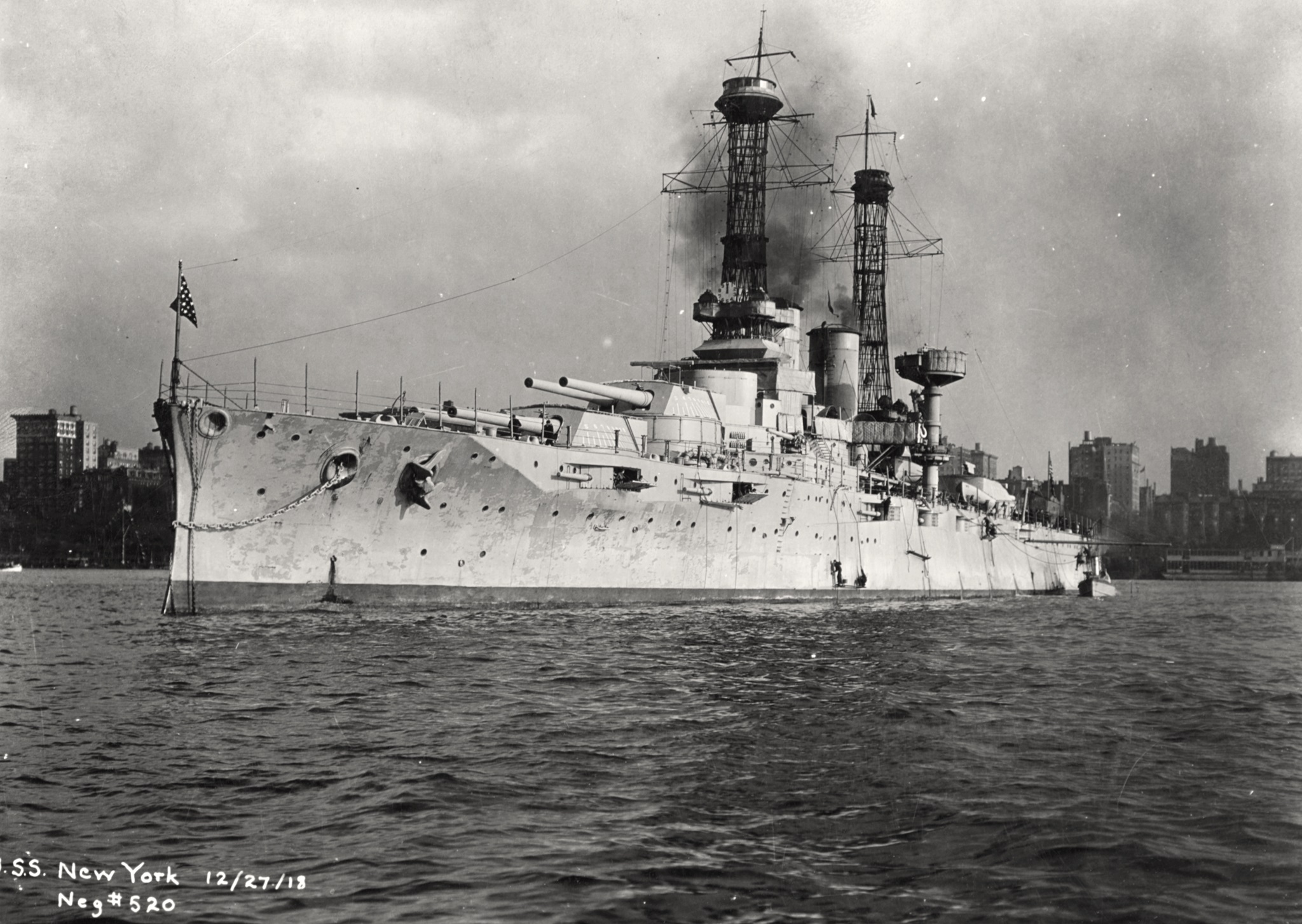

She was welcomed back home to New York City (where else) just in time for Christmas 1918.

Soon after, a commemorative bronze tablet was installed on her quarterdeck.

Celebrating New York’s Great War service, her image, shown steaming from west to east, was used on the reverse of the $2 Federal Reserve Bank Note, of which $136,232,000 worth of bills were printed between 1918 and 1922.

Interbellum and reconstruction

After just a few months stateside, New York was ordered to transfer to the Pacific Fleet, stationed out of San Francisco, which would be her home

USS New York (BB-34) in the east chamber, Pedro Miguel lock, during the passage of the Pacific fleet through the Panama Canal, 26 July 1919. NH 75721

USS New York (BB 34), aerial view of the battleship as she transits the Panama Canal. Photograph released July 1919. Note the details of her masts and secondary armament. 80-G-461375.

Sisters are back together again! USS New York (BB-34) and USS Texas (BB-35) Drydocked at the Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia, during the mid-1920s. NH 45153

USS New York, in the foreground, followed by sister Texas (BB-35), and Wyoming (BB-32), proceeding at full speed across the Pacific firing their guns during annual battle maneuvers. Courtesy of the San Francisco Maritime Museum NH 69006

By August 1926, she was sent to Norfolk Navy Yard for an extensive 13-month modernization.

This reconstruction gutted the old coal-fired engineering suite, replacing 14 original Babcock boilers with 6 more efficient oil-fired boilers, which of course required her bunkerage to change from one medium to the other. This resulted in her two stacks becoming one single stack. Her beam stretched 10 feet with the addition of torpedo blisters on her sides. Meanwhile, her lattice masts were ditched, and replaced by enclosed pagoda-style houses on shorter tripod masts, which dropped her overall height (from keel) from 199 feet to 186 feet.

USS New York BB-34 in drydock during refit at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Portsmouth, Virginia. 10 April 1927.

When it came to armament, her four torpedo tubes were removed as was most of her secondary battery (culling it from 21 5″/51s to just 6 guns, all above decks). Her 14″/45s were upgraded with their chamber volumes enlarged to allow larger charges to give an increased muzzle velocity, switching from Mark 1/2/3 guns to Mark 8/9/10 standard. For AAA work, she picked up eight 3″/50 DP guns arrayed four to a side. She also picked up the capability to carry, launch, recover, and maintain as many as four observation planes.

When she rejoined the fleet in September 1927, her mother would not have recognized her.

USS New York anchored in Hampton Roads on October 17, 1929. Note the single stack and rearranged masts, now with houses. NH 64509

USS New York (BB 34), port bow, while anchored, February 12, 1930. Photographed by U.S. Naval Air Station, Coco Solo, Canal Zone. 80-CF-14-2043-1

She was a favorite of the fleet, a showboat, and was often at the head of formations during this period.

USS New York (BB-34) leads USS Nevada (BB-36) and USS Oklahoma (BB-37) during maneuvers, in 1932. The carrier USS Langley (CV-1) is partially visible in the distance. NH 48138

USS New York (BB-34) leading the formation for fleet review in New York on 31 May 1934. Note how wide she is post torpedo blisters. This added 3,000 tons to her displacement and gave her and Texas a tendency to roll in heavy seas. NH 712

USS New York (BB-34) At fleet review in New York, 31 May 1934. Note the assortment of Curtiss floatplanes on her catapult. NH 638

New York attended the Coronation ceremonial naval review at Spithead in 1937 for King George VI, continuing her long link to the British royals.

More improvements would come. In 1937, she picked up two quad 5-ton 1.1-inch/75 caliber “Chicago Piano” AAA guns– thought state of the art at the time and were just entering service.

In December 1938, New York became the first American warship to carry a working surface search radar set. The experimental Brewster 200 megacycle XAF set, designed by the Naval Research Laboratory, ran just 15 kW of energy but its giant 17 sq. ft. rotating “flying bedspring” duplexer antenna proved capable of tracking an aircraft out to 100 nm and a ship at 15. By 1940, the XAF was modified to become the more well-known RCA-made CXAM, and the rest is history.

USS New York (BB-34). View of the ship’s forward superstructure, with the antenna of the XAF radar atop her pilot house, circa late 1938 or early 1939. Note the battleship’s foremast, with its gunfire control facilities; her armored conning tower; and the rangefinder atop her Number Two gun turret. NH 77350

She was going to need it.

Battleships of the New York-class, USS New York and USS Texas, in New York City during the New York World’s Fair, 3 May 1939.

War (again)

After the grueling Neutrality Patrol following the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, New York spent the beginning of the war escorting convoys between the U.S. and Iceland, which the Americans had occupied.

Occupation of Iceland, July 1941. Seen from the Quarterdeck of USS New York (BB-34), Atlantic Fleet Ships steam out of Reykjavik Harbor, Iceland at the time of the initial U.S. occupation in early July 1941. The next ship astern is USS Arkansas (BB-33), followed by USS Brooklyn (CL-40) and USS Nashville (CL-43). Note 3″/50 gun on alert at left, and quick-release life ring at right. 80-G-K-5919

Her AAA suite would balloon throughout the conflict to 10 quad 40mm Bofors mounts (40 guns) and another 46 20mm Oerlikons. She also saw her crew almost double, from her designed 1,069-man watch bill to one that grew to over 1,700 by 1944.

Early in the war, her Curtiss SOC Seagulls were replaced by iconic OS2U Kingfishers, which had a longer range and greater payload. She would put them to effective use.

Three Vought OS2U scout planes take off in Casco Bay, Maine, on 3 May 1943. Photographed from USS New York (BB-34) floatplanes seaplanes

Once the U.S. got into the war post-Pearl Harbor, New York was one of the few battleships left in the Atlantic. She was assigned to escort two further convoys to Iceland (16 Feb- 18 March 1942, and 30 April- 10 May 1942) as well as two to Scotland (in June and August 1942), alternating with Atlantic patrol duty looking out for the Bismarck– with both New York and Texas coming very close to the German boogeyman and her consort, Prinz Eugene.

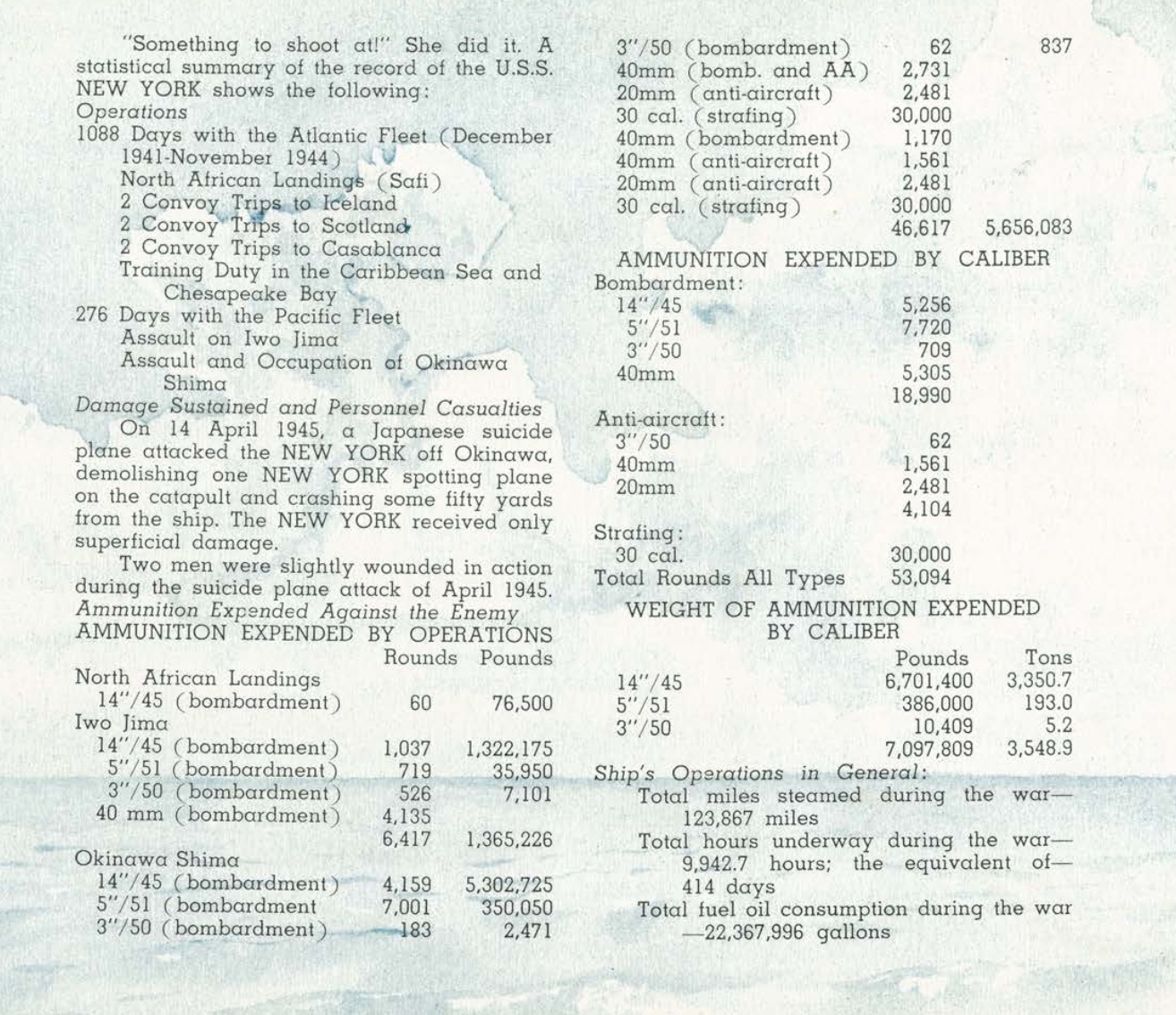

By November 1942, New York was tapped to help provide coverage to the Torch Landings in North Africa. There, off Safi, she fired 60 of her big 14-inch shells– the first time in anger– supporting the U.S. Army’s 47th Infantry Regiment ashore. During the campaign, she was straddled by French coastal artillery and, at Fedala, narrowly avoided German torpedoes.

Battleship USS New York (BB-34) Norfolk Naval Yard 11 August 1942 escort carrier USS Charger (ACV-30) just before leaving for Torch landings

USS New York (BB-34) off North Africa on 10 November 1942, just after the Battle of Casablanca. 80-G-31582

Once Torch was wrapped up, New York was used for two subsequent convoy runs (December 1942 and March-April 1943) between the U.S. and North Africa.

Across her six convoys (two each to Iceland, Scotland, and Casablanca), none of the ships under her watchful eye were lost or damaged by enemy action.

What a magnificent photo! USS New York (BB-34) pitching into heavy seas while en route from Casablanca on convoy escort duty, in March 1943. The view looks forward from her foremast. Note her twin 14″/45 gun turrets and water flowing over the main deck. 80-G-65893

USS New York (BB-34) in Casablanca Harbor, 1943. Photo from the LIFE Magazine archives, taken by J.R. Eyerman. Note that her radar and antennas have been airbrushed out

In March 1943, the Sultan of Morocco visited her.

Then came more than a year stateside, used for training.

She would serve as a floating Main Battery (14″/45, which was still used by sister Texas as well as Nevada and Pennsylvania while California, Tennessee, Idaho, and New Mexico had only slightly different 14″/50s) and Destroyer Escort Gunnery (3″/50, 40mm Bofors, 1.1/75 Chicago Piano, and 20mm Oerlikon) School from June 1943 to July 1944, steaming circles in Chesapeake Bay, and then, in the late summer of 1944, would be used for a trio of midshipmen training cruises to the Caribbean.

USS New York (BB-34) off the U.S. east coast, circa 1943, while a gunnery training ship. The only slightly older USS Wyoming would spend her entire WWII career in the Chesapeake on this duty. 80-G-411691

During this quiet period, New York trained approximately 750 officers and 11,000 recruits of the U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and allied forces as well as 1,800 Annapolis midshipmen.

Missing the landings in Italy and France, it was decided to shift the old girl to the Pacific in preparation for the last amphibious operations in the drive to the Japanese home islands. Leaving New York in November 1944– the lead photo of this post– she would arrive at San Pedro, California via ‘The Ditch” by 6 December.

USS New York (BB-34) photographed in 1944-45, while painted in camouflage Measure 31A, Design 8b. Note her extensive radar suite and annetaa array– which by this time of the war included SG, SK, and FC (Mk 3) radars as well as two Mk 19 radars– has not been airbrushed out. NH 63525

En route to Iwo Jima, she had an engineering casualty, with a blade on her port screw dropping that limited her maximum speed to just 13 knots and cramped her ability to maneuver. Nonetheless, New York still arrived in time for the pre-invasion bombardment of Iwo on 16 February and closed to within 1,500 yards of the invasion beaches to deliver rounds on target. She fired 1,037 14-inch shells in the campaign in addition to another 5,300 smaller caliber rounds (not counting AAA fire).

USS New York (BB-34) bombarding Japanese defenses on Iwo Jima, on 16 February 1945. She has just fired the left-hand 14″/45 gun of the Number Four turret. The view looks aft, on the starboard side. 80-G-308952

Able to get her busted screw repaired at Manus once the Iwo Jima landings ended, New York was in the gunline off Okinawa in late March, again in time to get in on the pre-invasion bombardment, providing NGFS to the U.S. Tenth Army and the Marine III Amphibious Corps throughout the month-long campaign, firing more than 4,000 14-inch shells alone.

Her aviation unit while off Okinawa was also amazingly active, with her three Kingfishers not only correcting fire from New York and 11 other ships on the gunline to support the Devils and Joes ashore, but they also fired 30,000 rounds of .30-06 in strafing runs on exposed Japanese targets– an unsung mission for Navy floatplanes.

Her closest brush with the Divine Wind came on 14 April 1945 off Okinawa when a Japanese plane came in amidships and crashed into a Kingfisher on the catapult. Incredibly, the Old Lady shrugged off the impact with only superficial damage– the bulk of the Japanese aircraft continued to come to rest in the ocean some 50 yards off New York’s starboard side–

and the ship listed just two personnel with minor casualties.

The Kingfisher damaged after being clipped by a kamikaze on 17 April 1945. The aircraft was later craned off ashore. NH 66187

Once the Okinawa operations stabilized, New York retired to Pearl to swap out her well-used 14″/45s for new ones in preparation for the upcoming invasion of Japan proper, Operation Olympic. She was there when VJ Day came, and those new guns weren’t needed.

She held to a quote attributed to Admiral Mahan, that, “Historically, good men on old ships are better than poor men on new ships,” with the words written on a sign on her quarterdeck.

Despite her extensive campaigning– from the Torch landings and screening convoys to bringing the pain in Iwo Jima and Okinawa– New York only earned three battle stars for her WWII service.

She made two fast trips shuttling personnel between the West Coast and Hawaii, then set sail for New York City on 29 September to celebrate Navy Day there along the “surrender ship” USS Missouri (BB-63) and the famed carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6).

USS New York (BB-34) arrives at New York from the Pacific, circa 19 October 1945. She was featured in Navy Day celebrations there later in the month. 80-G-K-6553

Of the 13 old battlewagons on the Navy List going into WWII, New York was one of only three that was never seriously damaged or sunk, despite the French coastal artillery, German torpedoes, and Japanese suicide planes.

During her career, she boasted that she had schooled the most flag officers– future commodores and admirals– than any other ship, a figure that stood at more than 60 by 1945. One thing is for sure is the fact that, of her 26 skippers, at least 10 went on to wear admiral’s stars.

Atomic Ending

Post-war, the Navy had three entire classes of ultra-modern fast battleships giving them eight of the best such ships in the world (Washington, North Carolina, South Dakota, Indiana, Massachusetts, Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, and Wisconsin) as well as eight legacy dreadnoughts that had undergone extensive modernization/rebuilds post Pearl Harbor (the 16″/45 carrying Colorado, Maryland, and West Virginia along with the 14″/50-armed California, Tennessee, Idaho, and New Mexico). Besides these 15 battlewagons, arguably the toughest battle line ever to put to sea, the Navy also had two more Iowas under construction (Kentucky and Illinois) and a trio of 27,000-ton Alaska-class battle cruisers (classified as “Large Cruisers” by the Navy).

This meant the service, which crashed into WWII with a dire battleship shortage, ended with a massive surplus.

As such, the older battleships that had not undergone as drastic a wartime modernization as the Pearl Harbor ships– USS Mississippi, USS Pennsylvania, USS Nevada, USS Arkansas, USS Wyoming, USS Texas, and our New York— were quickly nominated for either disposal or limited use as experimental ships or targets and rapidly left the Naval List.

The eldest, Wyoming, was decommissioned in August 1947 and sold for scrap by that October, preceded by her sister, Arkansas, which was sunk on 25 July 1946 as part of the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll.

This left New York as the oldest American battleship still afloat. She would not hold this title for long.

Like Arkansas, Nevada, and Pennsylvania, she had been used in the Crossroads tests.

USS New York BB-34 before Test Able during Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll – 1946. Note the Curtiss SC Seahawk floatplanes on deck and skyward-pointing 3″/50s. Most of her 20mm and 40mm mounts appear to have been deleted. LIFE Bob Landry

New York was just off the old Japanese battleship Nagato (to the right of the “X’) for the Able airdrop test.

And was the closest surviving battleship to the underwater “Baker” shot.

Somehow enduring both bombs, New York, Nevada, and Pennsylvania were towed to Kwajalein for decontamination (where Pennsylvania was later scuttled), then to Pearl Harbor and studied by radiological experts there for the next 15 months.

In the meantime, on 29 August 1946, the empty New York was quietly decommissioned.

USS New York (BB-34) entering Pearl Harbor after being towed from Kwajalein, on 14 March 1947. Note Floating drydock (ABSD) sections in the background. 80-G-371904

The experts satisfied they had garnered everything they needed to know from the mildly radioactive old battleship, it was decided to tow her out and allow the fleet a proper SINKEX in the deep sea off Oahu. It took them all day to send the leviathan to the bottom. Similarly, Nevada was towed out for the same fate a few weeks later.

ex-USS New York (BB-34) is towed from Pearl Harbor to be sunk as a target, on 6 July 1948. USS Conserver (ARS-39), at left, is the main towing ship, assisted by two harbor tugs on New York’s port side. 80-G-498120

ex-USS New York (BB-34) capsizes while being used as a target off Hawaii on 8 July 1948. 80-G-498141-A

Epilogue

While New York currently rests some 15,000 feet down, she has lots of relics ashore.

Her Chelsea chronometer, removed by a member of her crew before the Bikini tests, is now in the NHHC’s collection. As noted by the donor:

“By the time I left the ship, it was full of goats, rabbits, guinea pigs, and assorted other small animals that were to be on the ship at the time of the explosion. They were expected to survive as the New York was considerably more than a mile from the explosion. As I left the ship, I decided that I would save the clock we had in our quarters and put it in my bag. The New York survived the explosion- as was intended- as did all the animals- to the delight of the traditional navy. However, within one month all of the animals were dead.”

Her XAF-1 radar, the first installed on a U.S. Navy warship, has been in the collection of the National Museum of the U.S. Navy since the 1960s.

XAF Radar Antenna, 1960s. Being delivered to the Washington Navy Yard for display. Note the U.S. Navy tug alongside a small thin barge carrying the radar antenna. The tug appears to be USS Wahtah (YTB-140). This radar was the first shipboard radar to be installed onboard a U.S. Navy ship, USS New York (BB-34). NMUSN-1019.

Meanwhile, the antenna, which was delivered to the Washington Navy Yard by boat and is currently on display in the National Electronics Museum, Linthicum, Maryland after being displayed outdoors until the late 1980s.

The National Archives has her plans, deck logs, and war history preserved.

Her amazing 229-page WWII cruise book, from which many of the above images are obtained, is digitized online via the Bangor Public Library. It contains the best epitaph to the “Old Lady of the Fleet”:

Her sister Texas, of course, was preserved just after the war and is currently undergoing a dry dock availability to keep her in use as a museum ship for generations to come.

Out of the water! USS Texas at Gulf Copper 31 Aug 2022 Photo by Sam Rossiello Battleship Texas Foundation. Note the paravane skeg at the foot of the bow, her 1920s torpedo bulge love handles, and the stabilizer skeg on the latter.

Since BB-34 slipped beneath the waves in 1948, the Navy has since recycled her name twice, kind of.

USS New York City (SSN-696), an early Flight I Los Angeles-class hunter-killer, was commissioned in 1979 and retired (early) in 1997.

The seventh USS New York (LPD-21), a San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock built at Ingalls and commissioned in November 2009, is the current holder of the name. At 684 feet overall, she is larger and faster (“in excess of 22 knots”) than our battleship although she hits the scales at a paltry 25,000 tons– including 7.5 tons of steel salvaged from the World Trade Center.

This current New York carries several relics from the old BB-34, including her stern plate. It is displayed onboard the ‘phib under a 2-ton sheet of steel from the World Trade Center in the tunnel headed to the well deck.

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I am a member, so should you be!